Posted by Dave Bull at 2:42 PM, May 25, 2009

This is what you get when you put a little digital recorder in your pocket, clip a mic to your lapel, and head off into the nearby woods for a morning walk. (Some 'tech notes' are in the first comment, below ...)

So here we are, back in the RoundTable, with what may turn out to be ... another slightly overlong post! I did this the other day - started to post a short note, and ended up having it run and run ...

So, do I actually have so much free time these days that I can spend so much time on this sort of thing? I thought David was supposed to be so 'busy.' Of course David is busy, but it's that time when one print is finished, it's out for packing and shipping, the waiting desk work is done, the bookkeeping is done. Most of the email - not all of it for sure - is caught up on. The next job of course is - designing the next print!

For some of the prints in this series, I've known what I was going to do with it, quite some time in advance. But for some of the others, I haven't had a clue, and this is one of those. The next print - Forest in Summer - I don't have the slightest idea what to do.

So, instead of buckling down to it this morning, time for a bit of procrastination ... Let's see what comes out ...

When I set this RoundTable up some years ago, I chose that name for a specific reason, rather than name it 'Dave's Blog', or the 'Woodblock Blog', or some such thing. Because I had thought that what I would like to encourage was a kind of literal 'roundtable', where a group of like-minded people would chat together about the topics that were of interest. Not one guy at the head of a long table, putting things out and getting responses, but more of an environment where everybody put things into the mix.

But because of the way that the 'net works - people drop by and browse the pages, perhaps leave a comment if they feel so inclined, and then click away - there is actually nothing RoundTablish about it at all. Dave talks, and people sometimes add comments to that.

It's too bad. It's easy enough for me to try and encourage more participation, but perhaps it just can't be helped. This is just the way that the blog format works.

Anyway, we've got some time this morning, thanks to the procrastination, so let's put something down ...

I saw this TV program last night. As I have mentioned before, I have no TV, but one of my collectors sent me a DVD dub of a program on traditional printmaking that was broadcast recently on NH ... on a major national network here, thinking that I would be interested in watching it. I had actually already heard about this program, because it has received quite wide media coverage; it's been in the papers, people have been sending me emails about it, even my neighbours have asked, "Did you see that special program about the woodblocks?"

So yes, I was interested in seeing it, and set aside the time last night. But I tell you, by the time the ninety minutes were up, I was standing on my chair ... Cheering? No ... screaming!

It was about some woodblocks. It must be a few years ago, somebody in one of the distant rural parts of Japan, somebody from what must have been a wealthy family around a hundred years ago, unearthed from their storeroom a pile of woodblocks. They didn't know what they were, and actually, as we learned in the program, started splitting them up and using them as fuel for their wood stove. One day, one of the guys who was feeding the stove looked a bit closely at the piece of wood, and seeing how intricately carved the surface was, thought that it might be a good idea to perhaps check with somebody to see if this stuff could be useful to anybody.

Well, of course you know what happened; once word got out that these looked like old printing blocks from the late Edo period, the museum people descended in droves, and the blocks are now securely protected in a museum where they are being thoroughly studied and investigated.

It turns out that these are indeed blocks from the late Edo / early Meiji period. By investigating the designs carved onto them, they can be matched up with known prints from that time, many of which were designed by some of the big names from those periods, people like Hiroshige and Kuniyoshi. Now that alone would make these blocks 'treasures', but what really puts this whole thing over the top is the fact that these blocks show absolutely no signs of being re-printed in the intervening years.

The reason this is such a bit deal is that anytime old blocks surface here and there, as they occasionally do, they are invariably used for printing. People want to see the design, so somebody rubs pigments on and tries printing them. I even do this myself with blocks from a flea market; try taking an impression from them, to get an idea of what the print looked like. So whenever we do run across old blocks, we never really can tell just how old the pigment residue is. It could be ten years old, it could be a hundred; who knows.

These blocks though, are documented to have been untouched since the 'old days'. This is a real big deal for researchers who are trying to pin down just what materials were used to make pigments in the old days; what kinds of minerals, what kinds of plants, etc. etc. So these blocks are a fabulous treasure for them - a literal 'time machine' directly back into the old workshops.

They have been subjecting these blocks to all kinds of scientific analysis - X-ray diffraction, or spectrographic analysis, or whatever else they think is useful. And they are really getting results, finding that this was made with lead, this was made with such-and-such, and so on. This is a wonderful resource for them.

Now what they did next, either as part of the research, or to try and make the TV program more interesting, was to arrange for a contemporary printmaker to make a reproduction of one of these same designs (carving a fresh set of blocks, because of course nobody is now allowed to mess with these old ones), with the idea that for the printing, they would use these exact same materials for the pigments.

Remember, that all the old prints we now see in our museums and collections are hugely faded. Some of the pigments were 'fugitive', and lost their colour richness over time, while others were prone to oxidization, becoming blackened as the years go by. So a fresh reproduction like this would provide the world with a way to see exactly what one of the old prints looked like when it was first made, and when seen side-by-side together with one of the remaining copies of that design from a museum collection, would provide an exact 'measure' of just how, and in what way, the fading had taken place.

Great idea! And I really should have been standing on my chair cheering by the end of the program!

But instead, what happened next had me leaning forward to the screen, in shock at what I was seeing. They showed an outline of the process by which this craftsman had made his reproduction - tracing an original to get the outlines, then pasting that down on an block, carving it, then later moving on to the printing stage, etc. etc.

Before we can talk about what I saw, I have to speak about myself for a minute.

When interviewers came to me - this is going back many years - they would ask me, "What is the most difficult part of the process?" They kind of knew what I was going to say, and I too, stepped into their expectations, and usually replied something like, "Yes, it's the hairlines - these delicate ukiyo-e hairlines - this is the most difficult part!" Then I would describe it in the way that was expected of me:

"I save the hairlines for the last. I get myself in 'tip-top' condition; all the rest of the work is done, and I'm well 'warmed up'. I sharpen the knife very carefully of course. I then sit before the block. Take deep breaths. Then one by one, carefully - ever so carefully - I carve the hairs."

Now this is horse-radish ... absolute horse-radish.

Don't misunderstand; I wasn't lying to them, this actually was the way I myself was thinking at the time. But eventually, over years of repetitious work, I came to understand that this was completely the wrong approach to the job. Whether it is a juicy fat line in the image, or the most delicate of wispy lines, it makes no difference at all in the way you approach your work. You sharpen the tool in the way that will give the best result for the job at hand, then you sit down, pick up the tool, and cut the line. That's it, and that's all. No drama, no deep breaths, no fuss, no nothing. Just carve what you see.

If you approach the work full of tension - whether real or imagined - that tension will clearly be expressed in the finished work. Carving hair is no different than carving any other part of the block. Of course, there are techniques involved; you hold the knife a certain way, make the cuts in a certain sequence, etc. etc., but in 'mood' it is no different than any other part of the job.

But in this program, they just poured it on. I have no idea if it was the craftsman's idea, or something that the producers came up with, but they really made the episode into a mini-drama in its own right. He posed with the block in place on the desk in front of him ... gazed at what he was about to undertake ... dabbed sweat from his forehead ... he even held his breath as he started to cut. Drama, drama drama.

And it was a mess.

He started to carve; one hair ... two hairs ... And by then I'm yelling at the screen, "Stop! Stop! You're totally screwing it up!" The hairs were crooked, the way the knife was sharpened was totally unsuitable for the job, and it seems that even the piece of wood was not properly selected for this. It was a mess.

And yes, to my relief, he did stop. He laid down his knife, and said, "I can't continue. Let's stop."

When they asked him what was up, he gave the impression of casting around for something to say. He settled on the light. It was a cloudy grey day, and he said that the light wasn't good enough. (He actually had a nice bright light shining directly on his bench, but that didn't seem to be worth mentioning ...)

Now I can very much guess what was really going on, because I myself have been in exactly this same situation any number of times. It's that damn 'foolish pride' that always keeps getting in the way of things ... if you let it. Let me explain.

I remember making a visit to Ito-san the carver many years ago, in the company of a TV crew. They filmed a number of scenes where Ito-san explained some aspect or other of traditional carving technique to me. (As an aside, this was a wonderful opportunity for me, as I never had chances like this in 'real life' for learning from somebody like him.) As part of the program, they of course also filmed some shots of Ito-san carving alone at his bench. During these segments, I sat back out of the way, and was quietly amused to see that when the cameras were 'rolling', he never moved his block on the bench, but always waited until the camera had paused. He would use those momentary 'opportunities' to rotate the block into a more suitable angle for whatever he intended to carve next.

While the cameras were there, he also did no carving at all with the use of a lens. His eyes were actually very good, especially when one considers his advanced age at the time, but he did sometimes use a lens, and it was stored in plain view off to the side of his desk. Anyway, the point is that his 'public front' was actually a bit different from the way he did things day-to-day.

Please don't think I'm putting him down for this, or insulting him. He was a far better carver than I will ever be, and I respected him hugely. It's simply human nature to want to put one's best foot forward when being observed, especially when the cameras are running for posterity!

And 'back in the day', I did exactly the same things. I tried to avoid rotating the block while the camera was running, and I didn't let them see my lens (exactly the same type that Ito-san had). But as the years have gone by, I have felt a little bit disappointed in myself for the 'phonyness', however slight, and now no longer do those things. In fact, a couple of years back, when NHK was here to do another program, the lens stayed out in full view all the time, and they even took a number of shots looking down through it onto the block.

I am now 57 years old. Each of us ages in different ways, but one thing quite common to many people is the need for visual assistance as we get older. There is no way that I could now carve such hairlines without the use of that lens. I simply cannot do it. (This has perhaps has some influence in my decision to 'be honest' about such things, and to use the lens openly.)

The craftsman in the program is - as it happens - just my age; we were born in the same year. So, as I said a minute ago, I think I understand what happened that day while the filming was going on. He didn't want to be seen using the lens (or for all I know, perhaps the producer asked him to remove it), so tried without it. But he found that it just wasn't possible, so called a halt. Perhaps he was expecting to be able to continue privately after they left that day ...

As it happens, it seems that wasn't possible, because the program continued with the hair carving in the next scene, filmed on a sunny day. He had no choice but to proceed with it. And I'm sorry to have to report that it didn't get any better. When the camera zoomed in on the finished job, I had to bury my face in my hands, in sympathy with the carver. It was a complete mess: thin hairs, fat hairs ... long hairs, short hairs ... there were even hairs broken at the base. There is no way that anybody could publish anything printed from this block.

I'm shaking my head, talking to the guy on the screen, "Look, just send those media people out of there. They've got what they need now. Once they are out of the way, cut a new block, working in peace and quiet without the cameras!"

And that's exactly what happened. As they sat there on camera inspecting the finished block, he made a declaration that it was unacceptable, and that he would do it again. Dave here watching the program starts cheering loudly, "Yes, yes! That's the only way forward now!" The interviewer expressed surprise, but the carver was unwavering; it had to be done again. They of course presented this in the program as something wonderful - a craftsman so determined that the job had to be done perfectly, that he was willing to start right back at the beginning and do the weeks of work again.

We saw no more block filming. I presume he was left in peace to do the work, and when next we saw the results - in a shot of the finished block - the hair was much better, not great by any means, but better.

It may seem like I have been unfairly critical of the craftsman, but I know from experience how difficult things become once TV crews get into your workshop. He perhaps had not much control over what was going on there at all. I suppose the whole reproduction job was commissioned by the museum people in cooperation with the media, so the producer may have really been calling the shots all the way along.

So anyway ... this program has gone out into the world. It has been a very well viewed program, and has created lots of 'buzz' about our traditional printmaking world. And it's probably going to become a kind of standard 'reference', with these bright garishly coloured reproductions now setting a new standard about what is 'normal' for traditional prints. And of course this depiction of the carving, which completely distorts the 'cool and competent' professional approach of an experienced carver - let alone the results! - will be held up as an example of 'good' work.

Then you start to think about this; most of the people who will see this program - at least 99.999% of them - will of course accept without question what they saw. That carving? Well, it just looks like normal carving. The carver wiping sweat off his brow, deep in stress? Well, that's just the way carvers work. There aren't more than a couple of dozen people in this whole country who understand what they really saw. So I should just let this all go; it just doesn't matter. But part of me feels so frustrated that this sort of thing goes down into the future, and gets completely accepted as 'reality'. After all, if we had a chance to see such a thing somehow brought to us from the Meiji-era, we would of course accept it without question. "Ah, so that's how they did it back then!" Years from now, people will study this program, and say the same thing, "Ah, so that's how it was done back in the old days ... back in Heisei."

Part of me thus wants to stand up and yell, "No, no! Look, that's not how it is! It's like ... this!" And then show ...

And then show ...

But there's this 'creature' here in the room here with me; like a noisy little dog, 'Ego'. He's barking at me non-stop, "Grrr ... Ruff! Ruff! Dave, Dave! Grrrr .... Show 'em how it's really done! Ruff, ruff! Show 'em some of your blocks!"

And I'm sitting here trying to fend him off. "Ego, down boy! Down! ... Heel!" But Ego is barking, barking ... running around the room barking as he goes ... "Show your stuff! Show your stuff! Ruff, ruff," and comes climbing up my leg ...

I just yell at him, "Ego, get down off me!" Ego goes running off, and curls up on his cushion in one corner, but his legs are twitching, his whiskers are twitching ... his ears just won't stop twitching ...

Seems there's no way he's going to fall asleep just now.

So, instead of talking more about some other carver's work, let's just maybe try and placate little Ego somewhat here, before he chews my trouser leg off ...

I mentioned in the RoundTable post a couple of days ago, about getting an order for a set of the 'Beauties of Four Seasons' series, and mentioned in that same post the Utamaro print - the one that I had put in the freezer, when the printing work had to be interrupted. I wrote about taking them out and drying them off, and of course as I did so, this was another chance for me to look closely at them.

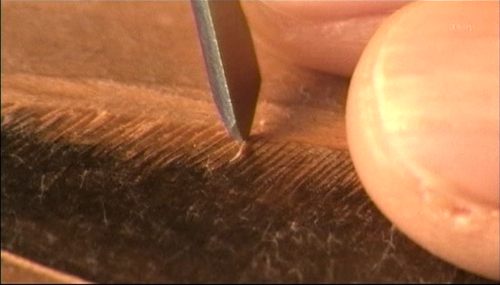

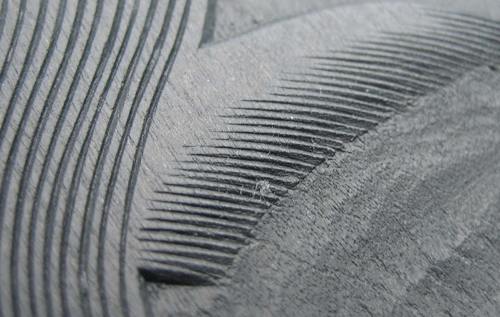

So this provided the impetus for me to dig in the storeroom and look for the set of blocks for it. I pulled them out, unwrapped then, and had a good look. Not sure what I can ... or should ... say next. Just here are a few photographs (clickable for enlargements).

The stars really lined up for me when I was making this one. I had a really, really good piece of wood. It actually made me a bit nervous, it was such a nice piece. I was thinking along the lines of, "Maybe I should put this piece aside; save it for when I have more skill. It's not such a good idea to give a nice block like this to a relatively inexperienced carver like myself." But actually, I already have some blocks in the basement, that I said that same thing about many many years ago.

I haven't thought of them in years, but there are a half-dozen 'special' blocks in my storeroom that have been 'waiting' for me to get 'good enough' since ... let's count carefully ... 1981. 1981! I bought them from block planer Shimano's san's father, who was still alive then. I had them shipped to Canada, where I was then living, and they came back to Japan when my goods were shipped over here in the mid 1990's sometime.

"One day. I'll use them one day."

So, given that background, it seemed like I could 'safely' use that good piece of wood for this Utamaro reproduction, so I went ahead with it. Whether inspired by the nice wood, or driven by fear of failure ... at this point I can't particularly say, but things went very well indeed, with results that you see in these photos. And in the finished print.

In that post the other day I used the phrase 'the best work I have ever done', which is something quite clear and measureable, but I also added '... and probably will ever do'. I was thinking of course, specifically of the 'fine line' aspect of the work. These days I am making originals, which by their nature, have no such delicate tracery. Over the past couple of years of making them, I have clearly felt a 'falling off' in the carving skills. (It was specifically to try and slow this slide, that I selected a delicate ukiyo-e type print for my new year card last year ...).

But another important point about that Utamaro block is that I did the way it should be done. I didn't sit there before the block in awe. I didn't hold my breath. I didn't make any fuss ... I simply prepared the block and tools, then sat down at the bench, and cut the lines. Not flippantly or carelessly, just ... what can I say ... with quiet confidence.

It's not really considered so acceptable to speak too highly of our own work - here in Japan particularly - but damn it, that block is magnificent. If you passed me such a block for inspection, I would be stunned into awe-struck silence just looking at it. It hardly seems conceivable that I actually did produce this object. Over the period of a couple of days that summer, I turned a blank slab of cherry wood into an astonishing work of art. I don't mean the finished print as a work of art, I mean the carved wood itself. The fact that it was then used to create some beautiful woodblock prints is kind of a peripheral bonus!

And - I might as well be hung for a sheep as a lamb - there's still more to it. That print required two almost identical hair blocks. In most ukiyo-e prints of this type, the hair is printed from two blocks - one in light grey (which has the individual hairs), and one in deep black (which makes up the bulk of the 'mass' of hair). But the men who created the original version of this print back in the 1790's worked out an interesting variation on this. They carved individual hairs at the edges of the dark black block also, lining them up one by one with the hairs cut on the delicate block.

This made the transition from deep black down to delicate invisibility much more effective. For the carver of course, it simply doubles the challenge. Actually, 'doubles' isn't quite the right word for it. A normal 'set' of hairlines on this kind of print is carved 'freehand'. The original designer didn't even attempt to draw them one-by-one, but simply indicated the area in which hairs were to be carved. So the carver normally has quite a bit of latitude, and can move along the wood, slicing them into place freely, without worrying particularly about where each one falls.

But in the case of this print, that freedom has been taken away. Because the two sets have to match up exactly, or the effect will be spoiled, the size and position of each hair must be followed perfectly. So after cutting the first set ... I had to cut another set, to match it. You have to carve with 'freedom' and with precision - two characteristics that simply do not mix.

As I said, it all came out pretty well (that photo just above, is my print).

Perhaps little Ego can now stop barking, and should be happy. Hopefully he'll go to sleep now and leave us alone for a while!

So I'm not sure where we've arrived, I've rambled along so much with all this. I know that none of these things should bother me; whether people think that program demonstrated masterful work or not, is kind of irrelevant. You skip ahead a hundred years or so, and what I would like to think is that by then, people just see the work, all they can see are the finished pieces of paper. And on that basis - TV programs aside - what can we say ... it sort of sounds overly dramatic ... but, the 'truth will out'! What's good will be recognized, and what's not will be set aside. I would like to think that's true.

But I suspect it isn't.

If the difference between 'good' and 'bad' isn't actually demonstrated, or taught: "Can you see this? Do you understand what you are seeing?", will the knowledge of the difference be lost? Does it matter? Or does my concern over these things all come down to my relationship with that little creature - the one now stirring again in his bed, with his ears twitching ... ready to begin barking again at any moment - is that what it all comes down to?

I'm not sure; really I'm not sure.

As I mentioned back near the beginning of today's ramble, I would like to have this RoundTable live up to its name a bit more, so I would very much like to hear views and opinions on this (admittedly vague) topic. And I'm not just 'fishing for compliments' here, for praise for my carving. I think that what I'm trying to get a handle on, is the question of whether or not it is important for the producers of work to try and train the consumers.

Or should we who make things be rather, completely 'disinterested', kind of in the legal sense of that word, as in 'not influenced by considerations of personal advantage'? Just put things out into the world, and whatever happens, will happen. Don't try to influence the way that things are received.

Is quality driven by the producers, or by the consumers?