Carving a Career From an Ancient Japanese Craft

David Bull, a 41-year-old Canadian university dropout born in England who used to program computers and play the flute on the street, anticipates one day finding himself revered as a master practitioner of an ancient Japanese craft. But it took him 35 years to hit upon that uncommon ambition.

He knows, as well, that once he completes his 10-year, 100-woodblock self-assigned mission to reproduce the famous bicentenarian set of representations of Japanese poets known as "Hyaku-nin Isshu" by Katsukawa Shunsho, he is not likely to win peer acceptance from the increasingly venerable (and therefore increasingly scarce) Japanese masters of the woodblock printmaking vocation.

And for now, he functions on the perhaps shaky assumption that by the time he reaches the zenith of his still nascent carving career he won't have entirely lost interest. It's happened to him before. "When I finish," Bull projects, looking ahead to (according to his schedule) the year 1998, "my skills will really be very high. They're good now, but obviously I'll be very good when I finish. By then there won't be very many people who can do it at all. There aren't now. And they're all very old. In another five or ten years they're going to be dead. It's quite possible that I could be a repository or quite a valuable skill. Assuming I still had an interest in it, I would perhaps be quite famous, my prints would command good prices, and I would continue. Pass it on to whoever wanted to learn it and I would be at this until I'm 99.

"The other street would be, when I get to the end of this to say, 'That's done. Now I'm going to do something else.' I can quite conceivably see myself doing that."

When he landed in Japan slightly more than seven

years ago (with his then-wife who has since reemigrated

to Canada) Bull made ends meet the same way as a plethora of native

English speakers. He taught English. Though typically, he went about

it his own way, opening a conversation school in his own home rather

than feeding his resume into the English-industry mill. He

complicated matters for himself by his refusal to teach from

textbooks, necessitating a liberal investment of time formulating

lesson plans - i.e. less time for woodblock carving, though the urge

to learn the hanga craft brought him to Japan in the first

place.

When he landed in Japan slightly more than seven

years ago (with his then-wife who has since reemigrated

to Canada) Bull made ends meet the same way as a plethora of native

English speakers. He taught English. Though typically, he went about

it his own way, opening a conversation school in his own home rather

than feeding his resume into the English-industry mill. He

complicated matters for himself by his refusal to teach from

textbooks, necessitating a liberal investment of time formulating

lesson plans - i.e. less time for woodblock carving, though the urge

to learn the hanga craft brought him to Japan in the first

place.

His initial goal was simply to earn his family's keep as a printmaker, an aim he has attained. Bull has 48 paying subscribers who for 10,000 yen per month receive 10 new prints per year (Bull makes one per month, except in January and August), each coupled with a written history of the print penned by the craftsman himself (in English, translated into Japanese by his wife).

Bull writed, edits and publishes a quarterly newsletter chronicling not only his own endeavours but those of craftsmen in related fields; for example, Kazuo Yamaguchi, manufacturer of the kozo washi (a special Japanese paper) onto which Bull transfers his woodblock images.

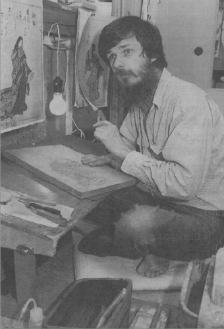

Carving the pictures onto finely planed blocks of wood from indigenous Japanese cherry trees, Bull uses only traditional materials and techniques. Except for a photocopying machine - rationalized by the fact that the original 200 year old image has to make its way from the ancient library book that Bull uses as a source to his woodblocks somehow.

Bull is tall and gangly with a gnomish thatch of beard and a forward-sweeping heap of chestnut hair that obscures a brow creased from, if not excessive furrowing (Bull doesn't seem the type given to bouts of fretting), than the easy eyebrow-cocking of the endlessly curious. He knows that no matter how advanced his proficiency he will forever, as a foreigner, draw the black ball from the fraternity of shokunin (craftsmen) specializing in hanga. At the same time, his life has passed through so many 'phases' that the lack of acceptance doesn't bother him.

The incessant bouncing around that has characterized his existence so far would never have been possible is he invested his identity with nationalities group memberships.

"I don't feel like a Canadian per se. That's just a place I happened to live for a number of years. Now I happen to live here," says Bull who dwells with his two daughters in a compact Hamura city apartment, with its only tatami room converted into a carving studio. "I don't really feel any particular nationalistic tie. I'm just a person right now. A woodblock person. So I don't really feel like an outsider here. You and I both know, from the Japanese point of view, of course, I am a complete outsider. But I don't feel that way.

"I don't feel like an insider either," he continues, speaking at this point of the select fraternity of woodblock printmakers. "I don't want to join their group. I'm technically a member of the association, but I'm not any kind of emotional member. I consider myself completely independent. Just someone who's developing a skill. So the concept of being an outsider or, how far in can I get - it never crosses my mind. A lot of those guys are friendly on the surface but there's a lot of rejection. I just let it roll off my back. I don't care."

Prior to printmaking, which caught his roaming eye while he lived in Canada, Bull's activities varied, centering loosely on music and computers. To commemorate his early exit from university his parents bought him a plane ticket and booted him out of the house. He spent a year in London engaged in what his resume describes as "informal studies in flute performance." In other words, he played on the street.

Practically as soon as he got off the plane at Heathrow, he spend the entirety of his meager bankroll on a flute. He opened his case for donations in front of a symphony hall and supported himself in moderate comfort with his musical talent (receiving frequent complimentary symphony tickets).

Upon returning to Canada, Bull whiled away 10 years in a variety of musical undertakings, none terribly successful, ranging from playing bass guitar for a Top 40 band to constructing classic guitars. His interest subsequently shifted to computer programming and he landed a job in Toronto where he "acquired an interest in things Japanese." Namely, woodblock printmaking.

He commenced studying the craft in Canada, but by 1986 realized that he could go no further without relocating to Japan. He was then 35 years old. So he packed up his family and off he went, on the trail of his latest enthusiasm.

This one has endured for more than a decade already, and his "Hyaku-nin Isshu" project is only about half complete. For a foreigner to forge a career from a nearly defunct Japanese craft may appear, to some, quixotic. But Bull who can now claim to pay the rent and feed the kids from income earned as a woodblock printmaker, finds that his exclusive group of followers are fascinated at least as much by him as by the colourful reproductions he turns out most every month.

"For those people who grew up in a structured, ordered society where people do things pretty much a certain way, to see somebody doing what I'm doing really is an eye opener," says Bull. "For them to see somebody finding his way through the universe in a different way than they know about is really enlightening and interesting. And it works both ways. I'm using Japanese tools, Japanese materials, Japanese techniques. Everything is really based on very traditional things in this society. Things that are gone now. Things that nobody else is doing. And for them it's nothing short of wonderful that somebody from another culture is sitting here picking up all these things that are being thrown away in Japan."

TV Listings

The 'Woodblock Shimbun' has a full selection of TV programs on file. Videos available include some of David's news appearances, complete feature programs, and some short documentaries on his work. The files are in QuickTime format, and can be easily viewed with your browser.

Program listings are on the Index page ... ![]()

'Youngest' Ukiyo-e Craftsman

Ukiyoe, the Japanese art form most familiar to foreigners, was not always highly appreciated. In its earlier days during the Edo period, ukiyoe prints were used to wrap fish, similar to how people use newspaper comics to wrap garbage. Though its reputation gradually improved, mainly due to its popularity with Westerners, it may be to no avail. Ukiyoe and the traditional woodblock printmaking craft is dying in Japan. With less than 40 members in the crafts guild, all of them over 60 years old, and no apprentices, this art form is close to extinction. (1992)

Full Story. ![]()

Woodblock craftsman combines old, new

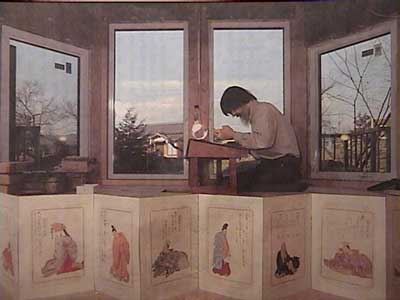

Day after day, David Bull sits in his workroom almost all day long using his energy to make hanga or woodblock prints. His workroom, housed in his four-story house standing on the side of a riverbank in Ome, Tokyo, has yet to be completed because he is building the room himself by taking time from his busy production schedule. (2004)

Full Story. ![]()

Shokunin vs Craftsman

During the seven years that I have been living here in Japan and studying woodblock printmaking, I have visited many shokunin and have enjoyed long discusions with them about their life and work. I have been surprised by many of the things they have said, and have come to realize that their thinking is sometimes quite different from my Western conceptions of a craftsman. (1993)

Full Story. ![]()