Woodblock craftsman combines old, new

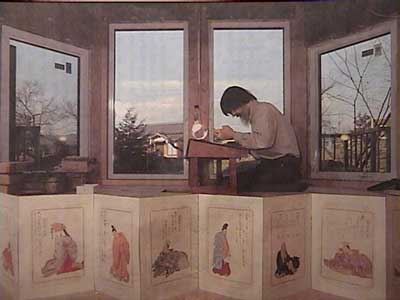

Day after day, David Bull sits in his workroom almost all day long using his energy to make hanga or woodblock prints.

His workroom, housed in his four-story house standing on the side of a riverbank in Ome, Tokyo, has yet to be completed because he is building the room himself by taking time from his busy production schedule.

After switching on a naked light-bulb above his worktable, the only lighting in the room, the 52-year-old woodblock craftsman grabs a chisel and starts to carve the woodblock. The chilly north-facing room apparently does not bother him once he becomes absorbed in his work.

"The work never becomes routine. It offers me endless challenges to overcome. " he said.

For more than 20 years, Bull has devoted himself to exploring Japanese traditional woodblock printing techniques. The hanga craftsman is one of a few artisans that use only traditional materials and techniques. Yet he does not strictly follow the original method.

Woodblock prints date back to the Edo period (1603-1868), creating a popular market in which ordinary people could participate. Hanga was not considered serious art. The original process uses a division of labor by a designer, a carver, a printer and a publisher.

But Bull does both the carving and the printing, which require an enormous amount of time and work. Despite a lack of knowledge about printmaking and formal training or apprenticeship, he found his own way to combine traditional and modern items in prints.

The subjects he chooses to reproduce vary from ukiyo-e prints by the world famous Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849) to a magazine illustration published in the Meiji era (1868-1912), a menu from a prewar transpacific liner and a print by a friend in the United States.

Bull said: "I make woodblock prints in a traditional way, but what I'm doing is something new. Although some people try to preserve dying traditional things, I don't feel that way. If the old arts and crafts don't meet the needs of people, they would naturally pass away."

Bull has been able to make a living from his woodblock prints, but not until 1991.

Born in England in 1951, Bull moved with his family to Canada at the age of 5, giving him dual nationalities. In his youth, Bull enrolled in a prominent music school in London and pursued a musical career as a flutist, but was not able to realize his dream. After he dropped out of college, his interest shifted to computer programming in music, and he got a job at a music store back in Canada.

In 1980, his first encounter with Japanese woodblock prints came at a gallery in Toronto. In his 20s, Bull became enchanted by the traditional arts and began collecting printmaking tools to produce his own prints. He eventually moved to Japan in 1986 with his Japanese wife and two little daughters to study woodblock printing seriously.

For several years, Bull made ends meet by teaching English while trying to improve his skills on his own.

"Living as a woodblock printmaker has not always been easy, but it has brought great satisfaction," the self-taught craftsman said.

His works initially drew public attention after he launched an ambitious project to reproduce a set of illustrations of the classical 31-syllable waka poems--Hyakunin Isshu (One Hundred Poems from One Hundred Poets)--designed by Katsukawa Shunsho (1726-1792), a ukiyo-e artist of the Edo period. Over a 10-year period beginning in 1989, Bull produced 10 prints of the series each year and sent them to subscribers.

He now has nearly 130 subscribers, enabling him to work as a full-time printmaker. But Bull said he had only about 10 subscribers when he started the project.

Recalling the 10-year period, Bull said the year 1993 was particularly tough for him as he got divorced and took custody of his daughters--Himi and Fumi. Raising children while working on the ambitious project was a great challenge to him.

Even under such circumstances, however, Bull said he did not consider leaving Japan. He continues to live in Japan although his daughters, now aged 20 and 18, work and study overseas.

"It's funny many people ask me if I plan to go home. But this country is my home. I have no intention to leave," he said with a laugh.

His ultimate goal is to show people in Japan and other countries how beautiful woodblock prints are by creating a new generation of prints.

The Internet has helped him achieve this goal. He created a discussion group on the Web through which members exchange opinions and information about woodblock prints. His Web site (http://woodblock.com), carrying his essays and quarterly newsletters, which offer detailed explanations of printmaking techniques and materials as well as the art's history, has served to introduce woodblock prints to people all over the world.

In fact, the number of overseas subscribers has increased and consists of about one-third of the total number of his subscribers, Bull said.

On Thursday, his 15th annual exhibition is scheduled to start at Gallery Shinjuku Takano in Shinjuku Ward, Tokyo. About 60 prints, such as from the Surimono Albums, his current project to reproduce a collection of privately published prints from the Edo period, and the Hyakunin Isshu series, will be on display. The exhibition will run until Jan. 27.

TV Listings

The 'Woodblock Shimbun' has a full selection of TV programs on file. Videos available include some of David's news appearances, complete feature programs, and some short documentaries on his work. The files are in QuickTime format, and can be easily viewed with your browser.

Program listings are on the Index page ... ![]()

Traditional Craft, Crisis or ... ?

As a worker in the field of traditional Japanese crafts, one of the most common things I hear from visitors to my workshop is, "Isn't it a pity that wonderful crafts like this are dying out nowadays." We sometimes tend to view traditional crafts as being superior to modern ways of doing things, but I have to wonder about this. I am sure that the craftsmen of old did not view their work in special terms. I think that they were simply people 'doing a job'. (1994)

Full Story. ![]()

13 Another Lucky Number

David Bull is as insistent as he is stubborn. No sooner has he sat me down beside his workbench (the only warm room in the house), with younger daughter Fumi (16) creating a Web page on the computer on top of the "kotatsu," than he is demanding how much I know about "hanga" (woodblock prints). "Hanga were never made to be framed and hung on walls," he states. "Premodern Japan had no such tradition. Prints were objects, not images, to be looked at in natural light. The best way for the art of the craftsman to be appreciated is in your hands, at a window." (2002)

David Bull is as insistent as he is stubborn. No sooner has he sat me down beside his workbench (the only warm room in the house), with younger daughter Fumi (16) creating a Web page on the computer on top of the "kotatsu," than he is demanding how much I know about "hanga" (woodblock prints). "Hanga were never made to be framed and hung on walls," he states. "Premodern Japan had no such tradition. Prints were objects, not images, to be looked at in natural light. The best way for the art of the craftsman to be appreciated is in your hands, at a window." (2002)

Full Story. ![]()

Japan and Me

"In 1775 an Edo bookshop published a series of portraits of the Hyakunin Isshu poets with illustrations by Katsukawa Shunsho, who was the leading designer of his day, just before Utamaro. We do not know if the book sold well or not, but few copies have survived and the book is extremely rare." (1989)

Full Story. ![]()