The Blue-eyed Ukiyo-e Craftsman

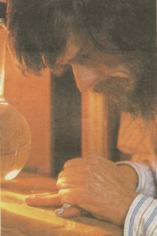

Midnight is the best time. The noise and confusion of the day's activities has died down, my two young daughters are lost in their dreams, the roar of the traffic passing on the road outside has dwindled away to an occasional murmur, and my hand is now steady and ready for the challenge. The easy parts are done, the kimono designs, the lettering, the outlines. Tonight I will carve the face - slicing away the rock-hard cherry wood sliver by sliver, and watching as the delicate features of a 10th century court lady gradually take shape in the wood.

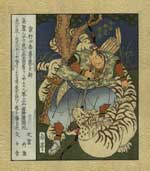

The image I am carving this evening, and which I

will start printing in a few days, is from a poetry book designed by

the Ukiyo-e artist Katsukawa Shunsho. Just about 220 years ago, he

was commissioned by a publisher to produce illustrations for the

famous 'Hyaku-nin Isshu' - One Hundred Poems from One Hundred Poets,

a collection of 100 works spanning the period from the 7th to the

13th centuries. These poems are no less famous in our day than they

were in his, with most reasonably well-educated Japanese people

knowing many of them by heart, and it is far from unusual to meet

people who have committed the entire collection to memory. They

represent one of the main pillars of Japanese literary

history.

The image I am carving this evening, and which I

will start printing in a few days, is from a poetry book designed by

the Ukiyo-e artist Katsukawa Shunsho. Just about 220 years ago, he

was commissioned by a publisher to produce illustrations for the

famous 'Hyaku-nin Isshu' - One Hundred Poems from One Hundred Poets,

a collection of 100 works spanning the period from the 7th to the

13th centuries. These poems are no less famous in our day than they

were in his, with most reasonably well-educated Japanese people

knowing many of them by heart, and it is far from unusual to meet

people who have committed the entire collection to memory. They

represent one of the main pillars of Japanese literary

history.

Unlike Utamaro's or Hiroshige's print designs, which have been reproduced endlessly over the years, Shunsho's remain relatively unknown. A few years ago I came across his book where it was sleeping in a research library in Tokyo, just about the same time that I was looking for a new printmaking project. One thing led to another, and I now find that I have finished thirty of the hundred designs. As each one is completed I send it out to the waiting collectors, the small group of people who are acting as patrons of this project. Carving and printing the remaining 70 will take me yet another seven years, and the final print in the series should be coming off my blocks in late 1998.

Woodblock printmaking in Japan has two faces. 'sosaku hanga' (creative printmaking), quite popular today, is the process by which a print is created in its entirety by one person, from design through carving and printing right to the final product. The other process, 'dento hanga' (traditional printmaking), uses a division of labour, typically four people - a publisher, an artist, and two craftsmen, carver and printer. In the Edo-era there was no 'sosaku' work, and all prints (and books, which were made with the same technology) were produced by these hired craftsmen, who numbered in the thousands. Of course, the arrival of commercial printing technology in the Meiji era destroyed the old way of doing things, and only tattered remnants of the system survive. There is a craftsmen's association still extant in Tokyo, made up of about 40 carvers and printers. Until a few years ago, these men made a comfortable living producing hand-made copies of famous old prints for the tourist souvenir market. That pretty much disappeared with the recent sharp rise in the value of the yen, and the handwriting is on the wall. With little demand for their products, with no young apprentices entering the field, and with materials and tools becoming increasingly difficult to obtain, the end of the more than 300 years of Japanese traditional printmaking history is in sight. Or is it? Although no young Japanese in his right mind will take on such archaic work, can somebody with bluer eyes perhaps have a role to play? I have been making woodblock prints for just about eleven years now, and unlike all other foreigners who are trying it (and there are quite a few of them) I have never had much interest in 'sosaku hanga'. The fascination for me is the smoothly-planed wood, the fluffy paper, the pigments being pressed deeply into the surface... I am a craftsman, an artisan, not an artist.

By taking on both jobs, carving and printing, I have my hands full. The craftsmen's association is made up of carvers who carve and printers who print, but never the twain .... Master carver Ito Susumu, now in his 70's, spent more than ten years as an apprentice. His printer friend Matsuzaki Keizaburo worked with his teacher for seven. These men help me. They are open, friendly, and unstinting with their advice. But inside, I have to wonder what they think about this 'gaijin' who thinks he can step into their shoes ... all four of them.

During my print exhibition every January (when I always take along my tools and give demonstrations of carving and printing), I find the reactions of the viewers I talk to invariably the same. Everyone expresses sadness that such an interesting and beautiful craft is dying out. But for myself, I really don't feel that way. As the world turns and new visions arise, the old must inevitably pass away. If a craft or other activity does not meet the needs of people in any given time, it must naturally disappear. Why then, am I doing this? Simple. It meets my needs. It offers me (in addition to providing a basic living), the fascination of an endless series of challenges to be overcome. The work never becomes routine or even predictable. I get an immense satisfaction out of producing the prints, and I suppose I have to admit that these feelings are strengthened by the knowledge that I am one of only a handful of people on this entire planet who are able to do this work.

Tonight's carving is done, and I lay down my knife and inspect the block. It has turned out well. The delicate hair is as fine as I have ever done - about four hairs per millimeter. I may feel satisfied with my skill, but I can never let myself forget some Edo era prints I saw in a carver's workshop one day, breathtakingly delicate, yet carved with supreme confidence. The memory floats in front of my eyes at this very moment. Will it be impossible for me to reach the level of those old craftsmen? I can't believe that, and will not believe it. Before I begin carving my next print, I will look at this one again with a critical eye, and I know I will see many places that it could be improved. I am on a long, long journey, but I can see my destination clearly in front of me, and I am yet young. Perhaps, if I am lucky, I will never arrive ....

TV Listings

The 'Woodblock Shimbun' has a full selection of TV programs on file. Videos available include some of David's news appearances, complete feature programs, and some short documentaries on his work. The files are in QuickTime format, and can be easily viewed with your browser.

Program listings are on the Index page ... ![]()

Artist Recreates Surimono Woodblock Masterpieces

Fascinated by the beauty of Edo-style woodblock prints, Canadian artist David Bull began carving and printing his own versions of traditional Japanese prints almost 30 years ago, just to please himself. Now living in Japan, Bull is one of a small group of craftsmen working to reproduce Japan's popular ukiyo-e and other woodblock prints. (2001)

Full Story. ![]()

David Bull: Printmaker

The classic woodblock prints made famous by Hokusai and others depict a stylized, long-lost Japan. A chance encounter with woodblock printing at an exhibition in Toronto more than twenty years ago led David Bull down a path that has made him the only artist, Japanese or foreign, working to reproduce those classical prints. (2000)

Full Story. ![]()

'Youngest' Ukiyo-e Craftsman

Ukiyoe, the Japanese art form most familiar to foreigners, was not always highly appreciated. In its earlier days during the Edo period, ukiyoe prints were used to wrap fish, similar to how people use newspaper comics to wrap garbage. Though its reputation gradually improved, mainly due to its popularity with Westerners, it may be to no avail. Ukiyoe and the traditional woodblock printmaking craft is dying in Japan. With less than 40 members in the crafts guild, all of them over 60 years old, and no apprentices, this art form is close to extinction. (1992)

Full Story. ![]()