Chinese Printing

The Chinese Printing Method

Here in Japan, whenever people start talking about the origins of anything in the culture, the conversation inevitably turns to China, and so it is with woodblock printmaking. Prints were being made in China from blocks of wood long before anything like that was done here, and the concept was obviously introduced here from overseas. But although the Japanese can't claim to have originated the idea, it is quite curious that almost all the techniques and ways of producing prints that became standard here, bear almost no relation at all to the corresponding techniques in China. Prints made with the two methods look so different that it is hard to believe that they share an underlying technology.

The Chinese, even though steeped in a similar calligraphic tradition, never went much for the brushed line, but instead focussed on masses of colour. And the tools themselves evolved in completely different ways.

And when one looks at the printing method itself, it is hard to accept the conventional wisdom that woodblock printmaking was imported to Japan from China. I find it much easier to believe that the concept itself travelled across the water, probably in the form of finished prints, and that the locals then went through a process of 'reverse engineering' to figure out methods of producing them.

The Japanese methods are described at length in other pages of this Encyclopedia. Here is a nutshell description of the Chinese printing method.

The pieces of wood used for each colour block are quite small, not much larger than the bare minimum needed to encompass the area needed. In many cases, the image is built up from tiny scraps and slivers of wood, arranged into the necessary patterns. These are placed on a flat table on which a bed of warm pine resin has been spread. As the resin hardens, the pieces become 'frozen' in place for the printing process.

Printing is done standing up at tables, and two of these are needed. There are no registrations marks used at all. The colour 'blocks' being printed at any moment are on one table, held in place in the resin, with other pieces of wood arranged around them to act as supports for the paper. On a separate table a stack of paper to be printed is nailed in place (the entire stack together) in such a position that the sheets can be 'flipped over' one by one to fall over the block.

The first few impressions serve to show how the tables must be moved to get the registration properly in place. Once printing commences, each sheet is flipped over in turn, and then after the impression is taken, it is dropped down into the gap between the tables, and the block re-inked for the next sheet.

A couple of notes:

- the paper is dry throughout the process, not moistened. Most Chinese prints were made on a thin 'gasen' paper, and a heavy printing impression was not necessary.

- the paper is oversize, to allow it to reach across the gap to the block. The extra is trimmed off after the printing is finished.

- due to the distance between the clamping point and the block, the registration easily 'wanders' a little. Chinese prints were not noted for the high level of sophisticated registration that their Japanese counterparts reached.

- instead of two tables, obviously one large table with a slot cut in the appropriate place could also be used - with the 'blocks' being placed on a board that could be moved for registration adjustments.

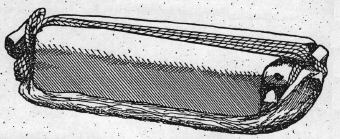

- bamboo skin is not used for construction of the baren, either inside or as a cover. A block of wood forms the main shape, and under and around this is wrapped a bundle of plant fibers (usually hemp), tied in place at the top with cord.