Yoshida Hiroshi : Print-maker : Part Two

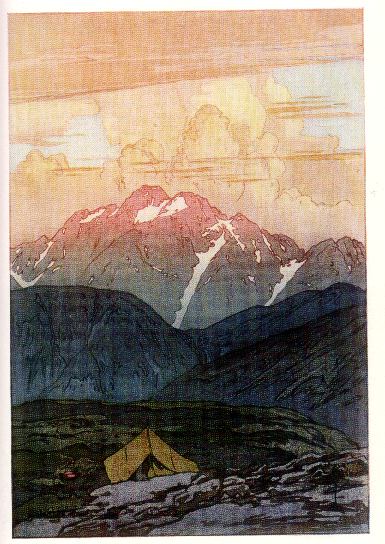

PERHAPS NO CONNOISSEUR WILL BE HEARD TO DISSENT from the judgment that Yoshida's greatest work is to be found in his prints of the Japanese mountains, from the fantastic peaks and crags of the Japan Alps, the serenity of Fuji or the autumnal quiet of Hakkoda-san to the grandeur of Rishiri, rising from its cold Northern sea. If one were compelled to the stultifying selection, from among so much beauty, of the one 'finest' work, one could do worse than to nominate the spectacular view of Tsurugi-zan flaming with morning, from the Japan Alps series - a choice which has at all events the merit of coinciding with Mr Yoshida's own preference among his prints.

Yoshida was, indeed, "in love with high far-seeing places"; mountains were the ruling passion of his life, artistic and personal. He looked so frail that he was sometimes called 'the Crane', but the appearance was deceptive; he was in fact an ardent and indefatigable alpinist. For thirty years, until his sixtieth year, he never omitted his annual summer's climbing-trip in the Japan Alps - where moreover he would pitch his tent or build his own hut of stone, becoming a temporary resident while for a month or more he climbed, sketched and studied peaks, coming home laden with ideas and plans for new paintings and prints. In 1914 he spent a month high up on Fuji-san (at and above the Eighth Stage, some 10,000 feet), living with lightning and thunder while he studied clouds. Among the books which he published was one, Kozan no bi wo kataru (Telling the Beauty of Peaks), in which he poured out this passion for mountains. "Mountaineering and pictures", he says in it,

to cut these out of my life has become a thing which I cannot do. Pictures are my trade; but as subject-matter for them nothing is so fascinating to me as mountain-scenes of any kind. The more you savor them, the more mountain-scenes come to have concealed in them a deep beauty. Seeking out the beauty of mountains, I have gone out, in Japan naturally, but also to the far Alps of Europe, the American Rockies and the Himalayas of India. For the next time, I am projecting without fail going to sketch the peaks of Africa.

Therefore, he said, although he had painted innumerable pictures of mountains, he had long cherished the desire "to pick out from among those the works after my own heart, but at the same time to put into words the feeling that I cannot express in pictures only, and to collect all into one book". The result is this most delightful volume, of discourse roaming over the mountains of Japan, Europe, America and Asia, their flora and fauna, the joys of bivouacking on mountains, the charm of the bases of mountains and their lakes, and many other points.

The artist's wife felt that the enthusiasm for mountains had gone out of control when the birth of their first son was greeted with the proposal to name him for the great peak of Haku-san of Kaga on the Japan Sea. She managed to avert their first-born's being addressed (with the addition of the usual suffix for 'Mr') as 'Hakusan-san', and he was called 'Toshi'; but when the second son was born, a real or fancied resemblance of the shape of the dome of his head to another famous peak elicited the suggestion that he should be christened 'Eboshi'. This time the mountaineer settled for 'Hodaka' - one of his favorite Japan Alps, but a mountain with a more mortal-sounding name.

Yoshida made sixty prints which are primarily views of mountains. Probably his best work altogether is collected in the two series Twelve Scenes in the Japan Alps, of 1926, and the six prints of the 1928 Southern Japan Alps Collection. Outstanding among these are the Morning on Tsurugi-zan [26], reproduced herewith, Yari-ga-take [84], 'The Five-Colored Plain' [30] and Hodaka-yama [28] from the earlier set; and Above the Clouds [106], Yatsu-ga-take after Rain [105] and Ma-no-take and Notori-dake [107] from the later. These prints illustrate perfectly Yoshida's mastery over both color and line, the management and placement of the mountain-masses and the peaks being given additional meaning by the stunning colors of clouds and skies. It must have been some such moment as the green sky and the mauve cone of Fuji floating on the cumulo-stratus sea of Above the Clouds which prompted someone, once, to ask Mr Yoshida, "Was it really like that?" The artist's ready answer, "Well, I felt like that", is an epitome of the creed which he had worked out for himself; he has said elsewhere, "It is not possible to be truly realistic in prints . . .. There should be no objection to making the trees black and the hills red, if the artist can express something worthy by that means. . . . colors that are not true to nature may be used in order to obtain a certain effect which the artist desires to produce".

Fuji-san could of course not fail of its share of attention from such a lover of mountains, and we have sixteen Yoshida prints of Fuji (in addition to two of those of the Japan Alps in which it appears in the far distance). The years 1926 - 1928 produced the Ten Views of Fuji, which include some of the traditional, as well as some more individual, scenes. Among them may be singled out for mention Musashino [69], capturing the distant prospect so familiar to Tokyoites; the magnificent winter view across the icy marshes bordering Lake Kawaguchi [61]; and The Sunrise-Rite [64], a whimsical scene in which appears nothing of Fuji san, but only the view outward into space at that moment of the sun's first rays, filled with a mystical meaning to the pilgrims who have made the ascent to the summit. Another of the set, Sunrise [62] - the mountain seen in the first light, from the plain - is notable as being the first block of the special large size ever attempted. Of the prints of Fuji outside this set, Fuji san from Gotemba [131] has a special interest in having been in part carved by Yoshida himself; it is details of the type of the irregular patterns and swirls of snow on the mountain-side which the print-artist usually finds it more satisfactory, as producing a feeling of more spontaneity, to carve freehand on the block rather than drawing them in detail on the original sketch for the carver to follow. Other examples of this type of work may be seen in the sunlight-effects in A Calm Day [144] and Ohara Beach [109].

Aside from mountain-scenes, one of Yoshida's most superb portfolios is the eighteen prints constituting the Inland Sea Collection of 1926-1927 and The Inland Sea series of 1930. The sketching for the latter series enabled him to pursue several of his hobbies at once: for the tour he engaged, in the summer of 1929, a small boat, complete with captain and cook (the boat is pictured in Waiting the Tide [143] and Three Little Islands [145]), and for two months made his leisurely way about the Inland Sea. When surfeited with work (and fishing, and sleeping) he would order the boat put into a port where he knew that he could find a go player - Mr Yoshida was 'rather strong' at go - and indulge that hobby until he was in the mood to resume the cruise. This languorous life is mirrored in the drowsy quiet of A Calm Day, Nabeshima [137], Morning at Abuto [142] and the rest of the set.

Any critical survey of Yoshida's work in color prints - which this essay does not pretend to be - would have to mention many other works taking high place by reason of their conception, or of execution, or for some other reason. The six sheets of Nikko [220 - 225], perpetuating that unrivalled combination of architectural opulence and lushness of nature; the Indian prints, of course, redolent of the pervasive color of that fabulous land [147 - 178]; and many less spectacular, more familiar things, part of the every-day life of Japan - The House of Plums [202], and the country festival at Kono [179], and Sarusawa Pond in Nara [187], and the Azalea-Garden [204] (Mr Yoshida's own). These and many others would have to be included - but they cannot be discussed here, and must be left for the collector to discover for himself.

WE SHOULD NOT CONCLUDE A REVIEW OF A COLOR-print artist's work without a word on his seals. The seal, ubiquitous and indispensable in Oriental life, inevitably has its great importance for the Oriental artist. The signature to color-prints normally takes the form which is usual in other departments of life: the signature in black (as if brush-written), with a seal below it in vermilion. Both signature and seal - known, collectively, as rakkan - may be cut on the blocks, or either or both may be applied separately. But whereas to the Western artist (always excepting a Whistler) the signature on his pictures is but an authentication, and to be placed with a view to inconspicuousness, to the Japanese it is an integral - and an important - element in the finished work of art. It is thus to be placed, not so that it shall be the least noticed, but in such way that it shall best add its own decorative effect to the composition; which involves consideration of its placement in the whole - whether at top or bottom, left or right, in an area of light or one of shade - of its size and shape, of whether it shall be pictorial or textual, and of its color, whether the conventional red and black or something different.

The Japanese artist's signature is usually his given name - whether the true one or an art-name which he has assumed - and his seal more often than not contains the surname, frequently in fanciful or punning form. Yoshida, however, reversed the process. His familiar vertical signature is 'Yoshida'

(the 'Yoshi' in hiragana, the 'da' in kanji); his seal is commonly some form of his given name, 'Hiroshi', most usual by far being the cartouche containing the character for 'Hiroshi',

... which is used, from 1925 to 1941, on some four-fifths of all the prints (two hundred three of them). This seal was one cut for Yoshida by his friend Matsumoto Issei, a painter. A variant form, cut by another painter friend, Takamura Masao, was used but once [138],

... as was another cut by the same artist, a seal spelling out 'Hi-ro-shi' in the old form of Man-yogana [124].

Second most common among Yoshida's seals was one in form of a 'kakihan', a 'written seal' or a sort of monogram,

... a type of signature of purely ornamental nature, but often constructed on some zodiacal principle and thus possessed of an esoteric significance. This seal was used by Yoshida in a variety of ways: in the large form illustrated, as well as in a much smaller version on his postcard-size prints; and on his maiden prints of 1921 and 1922 it represents both signature and seal. A felicitous special employment of it is to be found on a number of his wide-margined prints [124 - 136, 215 - 216], where the seal (usually accompanied by another, a representation of the printer's baren) is blind-stamped into the margin of the paper.

One other seal, used only occasionally by Yoshida but having a special interest, is the double one reading 'sairan', which exists in two forms.

'Sairan' means 'cutting brocade'; and the name was bestowed upon Yoshida by still another artist friend, Nakamura Fusetsu, to serve as an art-name with the implication that just as one might cut from an old brocade and preserve its most beautiful parts, so the color-print artist cuts out from nature and preserves the segments of greatest beauty. In the years from 1927 to 1929 Mr Yoshida used the two forms of this seal on a total of nine prints - seven of them larger than hosho, hence providing ample space for the imposition of a seal of more than twice the normal size; the remaining two, compositions with backgrounds of large expanses of solid color (in the one case the tile floor of a bath, in the other, snow) which can be enlivened by the graceful ideographs.

In three instances Yoshida employed seals having a significance special to the prints on which they were used. Four of his views of the Alpine region bear a dainty many-petalled flower

... which can be none other than the edelweiss of the Alps. The scenes from the Rockies are completed by a similar seal, representing the five-petalled American variety of this alluring alpine flower.

Third of these pictorial seals is one used on several of the Twelve Scenes in the Japan Alps, the komagusa,

...a flower of the genus dicentra which, found at high altitudes, serves in Japan as symbol of the high mountains as does the edelweiss in Europe. The komagusa may be seen growing in one of the prints of the set [36].

The remaining 'seal' used by Mr Yoshida is a small Egyptian symbol - the 'Ded' pillar,

... symbol of Osiris and thus connoting 'strength eternal' found only on his prints of The Sphinx [22 - 23], in conjunction with his ordinary seal. Two prints carry also a seal of the carver of the blocks [50, 62]. As a curiosity, it may be mentioned that most of the Indian prints have on the face of the print, in addition to the carved Japanese and pencilled English titles, captions in Hindi, Urdu, Tamil or Punjabi.

MR YOSHIDA HAS BEEN TREATED IN THIS ESSAY AS A print-maker, only. It is of course in that aspect that he is best known in recent years - abroad especially, where he has been the most widely-known and the most esteemed representative of the art of the wood-block. But while it is true that the best part of his life was devoted to work in that medium, he nevertheless always regarded himself as a painter working in various media and specializing in one; and in fact he continued actively to work in oils until the last year of his life. We are promised for the near future an exhibition of Mr Yoshida's output of prints; and for next year (his seventy-fifth anniversary) another, of such of his two thousand odd paintings as can be assembled. These exhibitions - which may be the last opportunity to see, outside museums, so comprehensive a collection of works of this distinguished master - should not be missed by any lover of the art of Japan, or indeed by any lover of art.

Nor have I spoken here of Mr Yoshida's personality - of how, deep in abstraction over a problem of art, he would adorn himself to receive guests by seizing upon his wife's sash and knotting it into his necktie; of how he delighted in playing with children, would spend hours amusing them with charades, performing masquerades, teaching them to recite 'Eenie, meenie, miney mo' of the students who surrounded him - came, indeed, from all the world to study with him - and his interest, never flagging, in their work and their doings. Of these things I have not written; but they will keep his memory green while those who knew him live.

Acknowledgment and thanks, for assistance in bibliographical and other questions, are due to Miss Dorothy Blair, of the Toledo Art Museum, Toledo, Ohio.