Yoshida - Japanese Woodblock Printing : Chapter III : Part I

Japanese Wood-block Printing

Hiroshi Yoshida

CHAPTER III

ADVANCED TECHNICAL ELUCIDATION (A)

Tools and Materials

The Studio

We have so far made general observations concerning the necessary steps connected with print-making. These, I hope, have given my readers at least a cursory knowledge of print-making. Now I wish to lead them to my studio and tell them about my work--how I go about it as a print-artist, what materials, pigments and tools I use; how I manage, or try to manage, the complicated intricacies connected with the work. By so doing I hope my readers may be able to get a real insight into the secret of making Japanese woodblock colour prints and secure a working knowledge of this branch of art the development of which has been peculiar to Japan.

Working on the Outline Drawing

To prepare the sen-gaki, or outline drawing, considerable time and thought are required. I often sit for hours at a stretch in contemplation. This usually occurs at the time when the azalea bloom is toward its end and the cherry trees, having no longer any blossoms, are covered with fresh verdure. The warmth and fragrance in the air tempt one to go out of doors and to ramble about. Naturally I look out of the window, gaze upon the blue sky, the passing clouds, the fresh verdure, etc. But my thoughts are on the prints I am about to start making. Many unfinished drawings will be scattered about in the studio, some on the floor, some on the table, and some pinned on the walls. This is the time when I dream over them. All sorts of beautiful results seem possible; the wonderful prints which are yet to be made are now visualized. Of course, some subjects seem easy to deal with; others appear hopelessly difficult, though tempting. Some seem very clearly defined; others are obscure in prospect. Some subjects may have taken my fancy for years, yet I may be unable to form a satisfactory drawing, the results so far attained lacking something somewhere. If I push my work in spite of such a feeling of dissatisfaction, failure is certain. That something which is lacking somewhere must be ascertained and supplied before I can go on.

Generally there are one or two drawings which stand out more prominently than others, and which seem to require immediate attention. They seem irresistible. So I begin to work on them.

Sometimes I go out on a trip somewhere into the country and sketch things which interest me greatly. If it happens to rain and this prevents my going out, I occupy myself in the inn in preparing a drawing for the print. Some of these attempts may seem satisfactory, but a further consideration of them is necessary after returning to my studio before I shall be able to complete the basic painting, or original composition from which the sen-gaki may be made. Many of the sketches, drawings, and paintings which are scattered about in my studio and to which I have referred above are of this nature.

Often in the evenings, when my mind may be tired, I find delight in returning to the contemplation of these drawings. I ask the opinions of the members of my family; often valuable hints are obtained from them, each from his or her own angle of observation. I have learned to respect these views. I understand that the great master painter Okyo, the founder of the modern realistic school of Japanese painting, often used to ask the opinions of farmers and artisans in order to perfect his art.

Finally I arrive at the stage where I think my original composition is all right. From this I make an outline drawing, having analyzed the picture in terms of colours and thought out all the necessary colour blocks connected with it. Then, and then only, do I proceed to have the outline drawing cut on the block to make key prints, or kyogo.

There is an inexpressible pleasure in the contemplation of the details in which I often lose myself. There is an endless delight in these dreams, for every dream seems bright and possible of realization. I deal with one subject at a time. Not until the outline drawing of one print is finished and the cutting well on the way, do I start on the next subject.

When I paint, sometimes I am so filled with enthusiasm that I can finish a picture in a day or two. During that time I shall be able to finish it completely so that it will be impossible for me to do any further work on it, not even to add a dot. But that sort of thing is not possible in print-making; it takes a much longer time to complete a print. Even after I have finished the outline drawing, it requires cutting and printing and many blocks have to be made for the colours, and all have to be printed in the proper order to obtain a finished product. It requires a long season of hard labour to get the final print.

Since such complicated and intricate requirements are involved in the process of making a print, it is necessary that there should be something strong and urgent in me to be expressed. There must be something that fills me with ardour; something that impels me to express myself in the prints.

In the Edo Period practically all the ukiyoye print-artists were poor, and had to struggle hard for a livelihood. They received very little for their drawings. Hiroshige seems to have spent in travelling nearly every sen he received. By actually being on the spot, associating himself with the subject directly, be it a landscape or otherwise, he was able to prepare himself for the work. When he had gotten himself deeply interested and full of enthusiasm he was able to produce many masterpieces.

Workshop for Cutting

When the sen-gaki is to be cut on the block, it is necessary that this enthusiasm should still exist. Cutting is tedious work. It is not done so quickly as the drawing. Every line requires two cuttings: that is, one on either side of it. And each has to be done very carefully, for an error will spoil the whole work. Once an error is committed, it is difficult to correct it. Not only when cutting the lines, but even in the sarai (clearing the space between), enthusiasm is highly necessary. The clearing is done with ai-suki, and it should be done even like Michelangelo's hammering away the unnecessary parts of the marble when sculpturing. A single wrong hammer stroke might have spoiled the whole work. It is the same with wood cutting. It takes a long time to finish even one block; sometimes many days. And there are many to be cut. And it is natural that the artist should like to see the result of his cutting, by printing it on paper, but he must wait until the end to get the impression. Thus it requires patience, yet his enthusiasm must not slacken until the end of the work.

Moreover, it is not impossible to keep up such enthusiasm that long. When I cut the block for my "Rapids" (1.8 ft. x 2.75 ft.) I was at it for more than a week at a stretch before I finished the cutting. I tried to express the force of the running water, the strength of the gushing river, the rush of the gurgling rapids. In order to obtain that result, I used a tsuki-bori, without paying strict attention to the drawing. I cut the block as my enthusiasm moved me, naturally disregarding the lines here and there. But I was so interested in the work that my ardour kept me at it until the end. Though I had to suffer physically for it afterwards, I was pleased with the result shown on the block.

In order to express natural phenomena by the lines in the print, it is necessary to study nature very carefully. To paint a river, one day may be quite sufficient, but in order to make the drawing for the print, two or three days may not be enough. It was only after careful observation that the true insight was revealed to me--the true insight obtained by some old masters who devised the conventional forms of crests of waves, etc., found in the traditional style of Japanese painting. At certain times the crests in the whirls of water look like fern sprouts, which curl and contort in various forms. Such a phenomenon the artist must study carefully before he is able to observe correctly, to draw and to cut.

The workshop where the cutting is done is liable to be far from neat. All sorts of tools will be lying about and the chips that fly from the blocks will be scattered about on the floor. It is impossible for the room to be kept tidy while one is at work.

At Printing Stand

The room in which the printing is done is also likely to be far from neat and tidy. All sorts of things will be scattered about--dozens of pots with pigments, various brushes for the colours, a basin of water, a pot of paste, another of oil, a board with shark skin stretched over it on which to split the hairs of the brushes, a bowl with the pigment which is being used and containing a brush for applying it to the block. There are rags also, these being necessary for moistening and wiping off the pigment from a part of the block for the shading. An assistant may be grinding powder pigment in a mortar, etc.

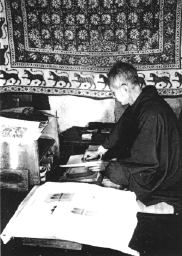

Figure 14

The Artist at Work

When the artist sits in front of the low table to begin work, he sits there cross-legged, as shown in the poses assumed by some Buddhistic figures. It is necessary that strength should be put into the lower part of the abdomen. This has long been insisted upon in Japan when one is engaged in some important work, whatever it may be. The attitude of mind must be right: it must be calm and well balanced. Of course, this need is not confined to the print-artist alone. It must be the same when a writer sits at his desk with a pen, or when a painter faces his canvas with a brush, or when a soldier is about to march against the enemy. Yes, the artist's mind then gets tense as if he were on the battlefield. Here indeed a battle must be fought in order to vanquish all difficulties and reach the realization of the ideal! While at work, the artist's mind must be kept intensely alert; every moment requires his closest attention. If this is not given, his work will be a failure. If a blot appears on one print unnoticed, then it is likely to be on every one of the whole pile of prints. This occurs when the artist works only with his hands, without the spirit behind them, without strength in his abdomen.

For printing a quiet room with a north light should be chosen, because in such a room the light is constant. Of course, a room with a south light is also necessary for drying purposes when the blocks are too wet, or for the purpose of warping the block. But for the printing studio it is better to have a north light.

In front of the artist there must be a box with a shelf for papers. Between this box and the artist is placed a low stand, tilted slightly towards the box and away from the artist. Upon this low stand is placed with the cut surface up the block which is to be printed; it should have cushions of rags at corners to make it steady and prevent it from slipping, and at the same time to give a soft springy effect when printing. There is another low stand on the left-hand side on which to place the prints after these are taken from the block. On the right-hand side is another low stand, for a dish of pigment with a brush, and a folded rag to be used for wetting the block in order to shade the colours. The rag is carefully folded with a piece of flat wooden board inside, so as to give a smooth surface when wetting the block. A small receptacle containing paste is placed on the other side of the block. This receptacle has a pasting stick inside.

The pigment is put directly on the block with a small tokibo; it is rubbed on the surface with the brush a few times, then a small quantity of paste is placed on the block with a stick, and rubbed together with the pigment with the same brush. This mixes the paste with the pigment and spreads the mixture all over the block.

Then the paper is put on the block, by fitting the right-angled corner to the right-angled register mark on the block and pulling the paper with the left hand to fit the edge to a straight horizontal mark near the left-hand side of the block. The paper is let down carefully on the block, and while one's left finger still holds the paper, the right hand reaches out for the baren, which rests on a piece of cotton containing a very little oil. The baren is applied first to the right-hand corner to fasten the paper to the block, and is then moved from one part to another. It requires many repetitions of the rubbing in order to get a satisfactory impression. After a few trials, one knows just how many rubbings are necessary, and a sort of regular path for the baren to proceed from one place to another in a fixed manner is established. This creates a sort of rhythmic motion, one's whole body swinging to the rhythm as his whole weight is applied to the rubbing of the baren. After sufficient rubbing the left hand seizes a convenient part of the paper and pulls it off the block and places it on the low stand on the left. These papers are piled one on top of the other face up so that one can examine each print as it is placed on the pile. With the removal of the paper, the head turns toward the left examining the paper to see whether there is any flaw, or an insufficient impression. Simultaneously the right hand is stretched out and places the baren on the cotton where it belongs without looking at it. One brushes the block with the brush when a fresh supply of pigment is given - there may be enough of it in the brush to last for two or three prints to spread the pigment, finishing the application by drawing the brush across the block, while the right hand returns the brush to the identical position where it is always placed, and catches hold of another paper to place it on the block. And the work is repeated over and over.

There will be an order, or regular sequence of motions established, which will be pleasing and easy for the artist. This order of motions in print-making will necessarily be different with each block. Some parts of the block may require three rubbings, another part four, and still another part five. In order to insure the exact result it is necessary to give the exact number of rubbings required for each part. It becomes a sort of formula to be followed each time. This is somewhat the same as the movements in cha-no-yu (ceremonial tea) in which great masters have prescribed a certain precise motion for each act, formulating a set of rules and fixing the sequence of motions in the performance of the necessary work. Only in that case the artistic effect must be considered, not only from one's own position but also from that of each of the guests in the room. Nevertheless, there is something similar in the two. In the printing there is a rhythm which the artist creates in the same general way with minor variations with each block from which he is printing. Again, as the host sits in front of the hot-water kettle in cha-no-yu, the artist sits in front of the block, with his attention fixed. He concentrates on what is to be done; he puts his whole strength and soul into the work. There should be nothing to disturb this concentration.