Visit to ... the papermaker's mother

Iwano-san's mother

Nearly a decade ago, back in the very first issue of this 'Hyakunin Issho' newsletter, I said "I plan to introduce you to some of the 20-odd other people who are involved in the making of the prints that you are collecting ..." In that same issue I then started this 'Visit to a Craftsman' series, with a short description of the work of Mr. Shintaro Shimano, the man who provides me with the blank woodblocks for my carving. Since that time, there have been a lot of visits in this series, and I have very much enjoyed meeting these people and introducing them to you the readers of this newsletter.

I had originally thought I would run out of craftsmen to visit long before the ten-year printmaking project had finished, but now that I am here just a couple of months from the end, I find it is exactly the opposite that is the case - I still have a long list of people to whom I want to introduce you. There are so many skilled craftsmen involved in the production of a woodblock print, that even in ten years, I haven't been able to cover them all in this series! I am beginning to think than even if I continued this series for another ten years, it wouldn't be enough time ...

But we'll leave such worries for the future. For now, let's drop in and visit another of those people without whose hard work and dedication these prints could not exist. Today's story will not be a very dramatic one, but it is about a very important person ...

* * *

First we have to step back in time about 70 years ... to a special day for the Iwano family of Otaki village, in the mountains of Fukui Prefecture - the day the new bride for the young man of the house arrives. The young man is the eighth generation of the family to work in the traditional trade of papermaking, and can we guess the young lady was perhaps proud to be joining a family with such a long history behind them, and with such a good reputation for their 'Echizen Washi' paper? But maybe she wasn't really concerned with such things - all her thoughts were perhaps about the young man whose partner she was about to become.

She well knew what it meant to become the o-yome-san for a family working in a traditional craft - that in addition to all her work as a homemaker, cooking and taking care of the family needs, she would have to carry a share of the papermaking work too. There would not be much rest for her over the coming years ...

Her life with that young man did indeed turn out to be a very full one. The war years of course brought considerable disruption to the family routines, but once things had become more stable after the war, the family found itself inundated with work. During the occupation years, and for a considerable period after that, woodblock prints were one of the souvenirs of Japan most prized by all the foreigners who then flooded the country. Of course, extra demand for prints meant extra demand for high quality paper, and the Iwanos worked 'overtime' to try and fill the constant demand.

The men of the family did the muscular jobs - beating the steamed kozo until the fibres were all separated, and the heavy job of dipping the actual paper itself, but there was plenty of work remaining to be done by the women. One of those jobs was that of picking out from the raw kozo fibre, the tiny pieces of dark bark that still remained in it.

The people who prepare kozo before shipping it to papermakers try to eliminate most of the dark outer bark, but plenty still remains, and it is essential to the quality of the finished paper that every tiny scrap be removed. In the papermaker's workshop the raw kozo is dumped into a vat of running water, and the person doing the speck removal then kneels in front of the tub, reaches in and swishes the kozo back and forth under the surface of the water, carefully inspecting each and every strand in turn, picking out specks as they appear.

As each clump of kozo is cleaned, it is removed from the water and placed on a board by the worker's side, but such is the importance of this step that one pass is not enough to ensure that all specks have been removed; the whole batch must be processed at least once more, either by the same person starting all over again, or by the next person in the group. The tub is usually long and narrow, and a few people can work kneeling side by side. Every member of a papermaking family becomes very familiar with this work ...

The water of course is extremely cold, and after no more than a few minutes of work, one's fingers become almost completely numb. For a standard batch of 500 sheets of printmaking paper, about 25 kilograms of the raw kozo will be needed. 25 kilograms - picked over strand by strand under this freezing water - twice over ...

This is the work that faced that young bride all those years ago, and this is the work that today as you read this story, 70 years on, she is still doing, day after day.

For that young lady soon became the mother of the baby who would grow up to be the Iwano Ichibei who makes the paper I have been using to make my prints for some years now. How many years they have been working together! I can imagine the little boy running around the yard and coming into the shed where his mother was kneeling with her hands in the cold water. He would say 'I can help you! Let me help!' and perhaps she would have let him pull at the kozo fibres until he became bored a few minutes later and ran off to play ...

But for her there was no 'running off to play ...' The collectors were waiting for their prints - the printmakers were waiting for the paper so they could make the prints - the papermaker was waiting for his kozo so he could make the paper ... They were all waiting for this lady to carefully finish her job cleaning each batch of kozo.

I suspect that if I tried to use the word 'dedicated' to describe this lady's approach to her work, she would laugh at me. She is simply doing her job as a member of a papermaking family. The man she married was eventually given the honour of being named a 'Living National Treasure' for his papermaking skills, and after he passed away her son became the head of the family - the ninth of his line. And on the day I visited some months ago, her grandson was also working at the vat beside her; it seems as though the line will continue ...

When I visited that day I had my camera inside my bag, and had fully intended to ask permission to take a few photographs that I could print together with this story. But as I stood there watching her work, I found myself unable to make that request. Over the decades of her life doing this job, she has had many many visitors. They come into the workshop, peer into the cold water to see what she is doing, and always exclaim 'Taihen desu ne eeee!' (What hard work this is!). They then take a snapshot and walk away, out into the sunshine. But Mrs. Iwano does not walk away with them. She remains kneeling at the vat, her hands moving the kozo back and forth under the surface of the water as her eyes carefully inspect every strand, searching for the tiny spots that must be removed. The minutes tick by into hours ... the hours become days ... and the days become years ...

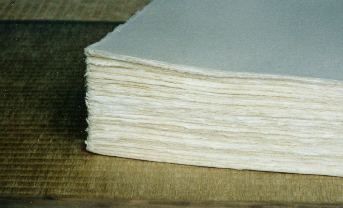

If I were to put her photo on this page, you the reader would be just like one of those visitors - you would peer over her shoulder for a moment, and you would then turn the page. But I don't want you to do that. Please put this story down for a minute, go to your shelf, and take down your set of prints. Lay the case on a table, turn off the overhead light, and then take a look at one of the prints. Do you see the soft and fluffy white surface of the paper? This beautiful beautiful washi ... Now close your eyes and think of this lady, with her hands in the water ... kneeling at that vat with her hands in that cold cold water ... for seventy years. That is why your paper is so beautiful. I could not simply 'steal' her image for this story. But I didn't need to - she is there in your room with you now, there in every sheet of that beautiful paper.

As you have come to understand from reading these newsletter stories over the years, there is a long chain of people behind each one of my woodblock prints. I, the man who signs each finished print and then passes it over to you the collector, am only the last link in this long chain. But I am no more important a link than any other. If any link were to be broken, the entire process would collapse.

I cannot show you her photograph, and I cannot even tell you her name, but I do hope you will join me in thanking this lady for her lifetime of hard work to help bring you these beautiful prints. Mrs. Iwano - we thank you very very much.