Visit to ... two young 'shokunin'

Two young 'shokunin' ...

During the nine years or so that I have been writing this little newsletter, I have visited many different craftsmen involved in the world of woodblock printmaking, and you have probably noticed that there are a couple of things that they all have in common: they have all been men, and they have all been ... well, if not exactly 'old', then certainly older than me. This month's guest is a little bit different on a few counts: for a start I visited two people rather than one; in addition they are both younger than me - a lot younger than me; and ... I won't be able to use the word 'craftsman' for one of them - it's going to have to be 'craftsperson' ...

This story is long overdue. Up until now, because I've concentrated almost exclusively on introducing you to older more experienced workers, you have probably picked up the impression that in a few more years when all those 'old guys' have passed away, traditional woodblock printmaking will be finished. I too have been guilty of thinking that way, and it's time to redress the balance - so meet printer Hiroshige Matsuzaki and carver Kayoko Koike. 'Old guys'? No way - even if you add their ages together, they still only have four more years than me - and I'm just 46!

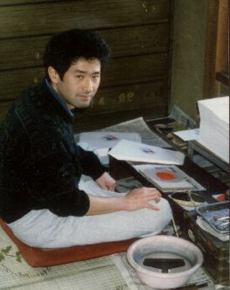

Those of you who have been reading these newsletters from the beginning will perhaps remember Hiroshige; he appeared for a moment in the story that I wrote about his father back in issue #4, although I wasn't so polite to him then - I showed only the back of his head in the photographs! At that time he was just getting started in this field, but he has now built up about ten years of experience as a printer, and as I talk to him I can sense that he feels much more confident about both his skills and his position as a member of this group of craftsmen. During these years of working together with his father he has made an awful lot of prints, of many different types, and has learned many techniques about which I still know nothing. But even after ten years of training it seems that he still considers himself to be an apprentice, and tells me that it will probably be another five years or so before he becomes ichi nin mae, a craftsman in his own right.

Those of you who have been reading these newsletters from the beginning will perhaps remember Hiroshige; he appeared for a moment in the story that I wrote about his father back in issue #4, although I wasn't so polite to him then - I showed only the back of his head in the photographs! At that time he was just getting started in this field, but he has now built up about ten years of experience as a printer, and as I talk to him I can sense that he feels much more confident about both his skills and his position as a member of this group of craftsmen. During these years of working together with his father he has made an awful lot of prints, of many different types, and has learned many techniques about which I still know nothing. But even after ten years of training it seems that he still considers himself to be an apprentice, and tells me that it will probably be another five years or so before he becomes ichi nin mae, a craftsman in his own right.

Kayoko san has not been carving that long; she joined this trade after graduating from high school three years ago. She told me that the first carving jobs she was given were woodblocks filled with texts from nagauta, a very old type of traditional singing, and I was a bit surprised to hear this, because I have read that this is exactly how a carver's apprentice was started off hundreds of years ago. But she said that carving these bold cursive characters is a very good way to develop one's skills at working the knife around curves in every direction, without moving the block. This is exactly the kind of disciplined training that I have not had, and I envy her the firm foundation she is developing. This made me wonder if her oyakatta, the man from whom she is learning, is an old-fashioned strict teacher, but it seems that he is approachable; she is not being left to figure things out for herself, and her working environment is open and congenial.

Kayoko san has not been carving that long; she joined this trade after graduating from high school three years ago. She told me that the first carving jobs she was given were woodblocks filled with texts from nagauta, a very old type of traditional singing, and I was a bit surprised to hear this, because I have read that this is exactly how a carver's apprentice was started off hundreds of years ago. But she said that carving these bold cursive characters is a very good way to develop one's skills at working the knife around curves in every direction, without moving the block. This is exactly the kind of disciplined training that I have not had, and I envy her the firm foundation she is developing. This made me wonder if her oyakatta, the man from whom she is learning, is an old-fashioned strict teacher, but it seems that he is approachable; she is not being left to figure things out for herself, and her working environment is open and congenial.

Kayoko san and I have one thing in common, the fact that people use the word mezurashii (unusual) to describe our situation. But just as I would rather be judged on the quality of my work rather than on the colour of my hair and eyes, she doesn't feel that her gender makes any difference at all; she is a carver - a shokunin.

As the three of us sat chatting in a restaurant the other day, it became apparent to me that she is perhaps the one who is the most authentic shokunin; when I asked whether or not she felt that her name should appear on the finished prints, she felt that it wasn't important, it was just her job to carve the blocks. For me of course, it is essential to have my name there, and Hiroshige too felt that he doesn't mind his name being attached to work of which he is proud. I think this is perhaps more common these days, after all, so few people are left who can do this job, isn't it right to feel some pride at being one of them?

One thing that I found very exciting and refreshing when talking to these two young craftsmen (ok, 'craftspeople' ...) is that they were both very optimistic about the future of their job. Now maybe you will say 'Of course they are, they're so young!', but it is more than just the enthusiasm of youth, it is a confidence that society will find their skills worth supporting. The economy will go up and down as it always does, and there might be lean years sometimes, but in the long run, the work they do will be judged valuable. I myself have that confidence, but it is not universal, and I was thus happy to hear it from these two ...

One thing that I found very exciting and refreshing when talking to these two young craftsmen (ok, 'craftspeople' ...) is that they were both very optimistic about the future of their job. Now maybe you will say 'Of course they are, they're so young!', but it is more than just the enthusiasm of youth, it is a confidence that society will find their skills worth supporting. The economy will go up and down as it always does, and there might be lean years sometimes, but in the long run, the work they do will be judged valuable. I myself have that confidence, but it is not universal, and I was thus happy to hear it from these two ...

The division of the process of making traditional woodblock prints into separate workshops - carver and printer, means that there is sometimes not much chance for workers in the two fields to communicate with each other. So our dinner conversation together was especially interesting - and we filled up a few napkins with scribbles of just how a woodblock carved some particular way would affect the way that it was to be printed. I am sure that the people at the next table in the restaurant had no idea what on earth our discussion was about. It was an interesting interchange, and I hope that we can spend more time together in the future. For me there is only one problem with this; whenever I go and see most of the craftsmen in this field, I always come away from the visit feeling very young indeed, but after talking with these two ...

Hiroshige-san, Kayoko-san, I wish you every success in your future work, and hope that woodblock printmaking brings as much happiness and satisfaction as to each of you, as it has to me.