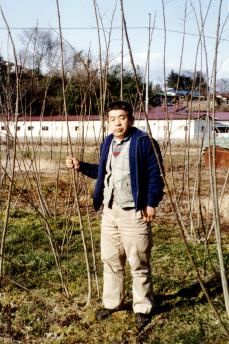

Visit to ... Souma-san, mulberry supplier

Mr. Teruo Souma

I should have realized that this visit would be different from the typical 'Visit to a craftsman ...' when Souma-san phoned me up to ask when I would be coming .... a strong, assertive voice with machine-gun delivery. I was being somewhat hesitant about making the trip to see him; it was a long way to go, I was very busy, and right now I really couldn't spare either the time or money that it would cost me to get over to the far end of Ibaragi Prefecture.

He was

audibly disgusted with my hesitation. "Well, are you coming ....?" He

obviously wanted to get this thing organized, and get back to his

work. I made my decision to head over there, and we made the

arrangements, but when I hung up the telephone I shook my head in

wonderment ... this just didn't sound like the kind of person who

would ever have the patience to sit there for hours at a time peeling

the bark from steamed mulberry branches in order to provide

Yamaguchi-san with the raw material for his paper-making work. What

would I find when I got there ...?

He was

audibly disgusted with my hesitation. "Well, are you coming ....?" He

obviously wanted to get this thing organized, and get back to his

work. I made my decision to head over there, and we made the

arrangements, but when I hung up the telephone I shook my head in

wonderment ... this just didn't sound like the kind of person who

would ever have the patience to sit there for hours at a time peeling

the bark from steamed mulberry branches in order to provide

Yamaguchi-san with the raw material for his paper-making work. What

would I find when I got there ...?

I left the house at 5:15 in the morning, and five trains and five hours later I alighted at Fukuroda station on the Suigun line running north from Mito City. Souma-san in person was just like Souma-san on the telephone. Brisk, and 'no-nonsense'. A man in a hurry. "Grab your camera. Let's go." And for the next four hours or so, we 'went' ... non-stop. I got the 'grand tour' of his whole operation - from fields to finished bales. Of course he's got no patience, he's not a craftsman, he's a businessman!

Actually, there is a reason for all the hurry, and that is the seasonal nature of the process. There's only a short 'window' during which this work can be done. Cutting the branches off the mulberry trees starts right after New Year, and continues for only about two months.

After harvesting, the branches are trimmed to

length (about 70cm), bundled together, and steamed for about two

hours.

After harvesting, the branches are trimmed to

length (about 70cm), bundled together, and steamed for about two

hours.

As the softened branches come from the steamer, a

group of workers quickly detach the outer bark from the wood. This is

done by hand with a quick twist on the end of each stick to release

the bark, and then a sharp tug to strip it off. The wood itself is

not needed and is sold for use in making the strips that bind

traditional wooden buckets.

As the softened branches come from the steamer, a

group of workers quickly detach the outer bark from the wood. This is

done by hand with a quick twist on the end of each stick to release

the bark, and then a sharp tug to strip it off. The wood itself is

not needed and is sold for use in making the strips that bind

traditional wooden buckets.

A large open barn nearby is jammed with rack

after rack of bundles of the stripped bark, waiting to be taken up to

farmhouses in the nearby mountains, where the most labour-intensive

step takes place, separation of the unwanted dark outer bark from the

white inner kozo fibers. Souma-san drove me up there to show me the

process.

A large open barn nearby is jammed with rack

after rack of bundles of the stripped bark, waiting to be taken up to

farmhouses in the nearby mountains, where the most labour-intensive

step takes place, separation of the unwanted dark outer bark from the

white inner kozo fibers. Souma-san drove me up there to show me the

process.

This was more like what I had expected to see. An

ancient, weather-beaten old country house. Of course a huge thatched

roof. And under the eaves outside, protected from the cold wind but

exposed to the winter sun, a wide bench with four 'work stations'

where a trio of grandparents sat working. They do this on a piecework

basis for Souma-san every winter, and have obviously been at it for

many years. There's no 'go go go' tension up here, and I'm sure the

three of them (one was off for the day) expended far more calories in

laughter at their companions' remarks than in actual work. They get

it done though, and the row of fat bundles of cleaned kozo drying on

a bamboo pole testified to how early this morning they must have

started.

This was more like what I had expected to see. An

ancient, weather-beaten old country house. Of course a huge thatched

roof. And under the eaves outside, protected from the cold wind but

exposed to the winter sun, a wide bench with four 'work stations'

where a trio of grandparents sat working. They do this on a piecework

basis for Souma-san every winter, and have obviously been at it for

many years. There's no 'go go go' tension up here, and I'm sure the

three of them (one was off for the day) expended far more calories in

laughter at their companions' remarks than in actual work. They get

it done though, and the row of fat bundles of cleaned kozo drying on

a bamboo pole testified to how early this morning they must have

started.

After I got my pictures, one of them took a

break, sat us at the old 'irori', and offered us tea and a bite. And

what a bite! Country-style 'yaki mochi', tsukemono, and vegetables. I

guess I forgot myself and showed a bit too much pleasure at the mochi

(which was way, way more tasty that the usual bland white type that I

am used to), because next thing I knew, there was a bundle of them in

my shoulder bag. (It wasn't until we were on our way down the

mountain that I realized that I was probably carrying everybody's

lunch with me!)

After I got my pictures, one of them took a

break, sat us at the old 'irori', and offered us tea and a bite. And

what a bite! Country-style 'yaki mochi', tsukemono, and vegetables. I

guess I forgot myself and showed a bit too much pleasure at the mochi

(which was way, way more tasty that the usual bland white type that I

am used to), because next thing I knew, there was a bundle of them in

my shoulder bag. (It wasn't until we were on our way down the

mountain that I realized that I was probably carrying everybody's

lunch with me!)

I'm not quite ready for it yet, but when it's my turn to be 80-odd years old, I don't think I'd be able to find a more congenial way to pass the time than to sit in the sun with a group of friends, doing a productive job like this ... one that nobody else wants to do, but yet which is absolutely necessary for the process of making beautiful woodblock prints.

Back down at the main workshops, the clean kozo is then carefully bundled up for shipment to waiting paper makers. And that's it until the next season. There's no re-planting to do, as the plants simply sprout up again automatically in May. During the year there's almost no maintenance. There's no spraying, as there are no insects attacking the kozo in this area, and only a very simply quick hand pruning (snapping off unwanted shoots). But for these ten weeks or so ...

These people don't just sleep for the other nine months of the year. Growing in the same fields, spaced between the mulberry trees, are 'konnyaku' plants ... but I don't think we'll get into that story here ...

Souma-san is the third generation of his family working with 'kozo' in this valley, one of the most famous places in the country for mulberry production. His grandfather moved here from Fukui Prefecture, and Souma-san still has relatives living back there, quite near to the paper maker Yamaguchi-san. He ships his product to paper-makers in many areas of Japan, and he ships a lot of it. Handmade paper may not exactly be a 'growth industry' these days, but it is a very important part of Japanese life, and there is good demand for quality kozo. The major problem facing Souma-san is finding workers willing to take on such labour-intensive work, even on a seasonal basis. As the population in this rural area drops steadily year by year, finding workers gets ever more difficult.

He dropped me back at the station in mid-afternoon, and the same five trains (but about six hours this time) got me back home again, just in time to see my daughters before they went to bed. They'd been quite excited about the idea of spending the whole day by themselves, right from breakfast to bedtime, but had had no problems. And in case anyone has any doubts as to whether my kids have really become Japanese or not, they thought the 'yaki mochi' was just about the best present I could have brought home for them!