Visit to ... Misawa-san, paper sizer

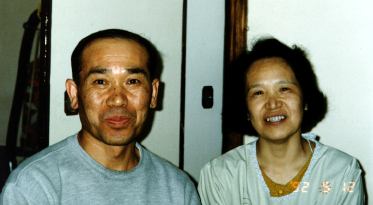

Mr. Isami Misawa

Crocodile skin! I couldn't believe my ears. I knew that shark skin is used in printmaking, but this was the first I'd ever heard of crocodile skin (wani kawa) being utilized by traditional printmakers. A hundred questions instantly bubbled up in my mind. How on earth did the Edo craftsmen ever get hold of such a product? What will my collectors think when they find out about this? Why had I not heard of this before?

Misawa-san saw the obvious confusion on my face. He patiently started to explain again what ingredients were in the liquid sizing that he was brushing onto each sheet of paper. 'Myoban' (alum) I understood. But 'wani kawa'...? And then the penny dropped. Not wani kawa, crocodile skin, but wa nikawa, Japanese glue. What a relief!

Everybody pretty much understands that my prints are made on Japanese hand-made paper ('washi'), but what is not so well-known is that it must be processed a bit before I can use it for my work. After the Yamaguchi family has finished making the paper to my specifications, they send it to Mr. Isami Misawa, who 'sizes' the sheets one by one with a glue-like mixture, and gives them the strength to stand up to the repeated rubbing with the printing baren. One day this spring, I made the trip over to his workshop in south-eastern Saitama to get better acquainted, and to see something of how the work is done.

Not

all of the conversation went as badly as the episode just recounted,

and I spent a very enjoyable afternoon watching the work, and

listening to Misawa-san and his wife Hisako tell me about what they

do. Unlike almost all the craftsmen who have a part in my project

(including me), Misawa-san works standing up. Some of his soft goat

hair brushes are almost a full meter wide, and there is no way to

handle such tools sitting down. A trough full of the warm size stands

at the right end of his bench, and the stack of soft 'raw' washi is

placed in front. He works on a batch of about five sheets at a time,

covering first the front sides, then flipping them over to do the

back, thoroughly saturating each sheet. The morning's stack of a few

hundred sheets is then allowed to stand and 'even out', and in the

afternoon the sheets are hung in pairs from the million cords

stretched across the ceiling. Hisako comes upstairs to help him with

this. Two hands are just not enough for this job, as the soggy paper

must be held very carefully in order not to allow creases to form.

They have been doing this together for a long time, and their 'dance'

is well rehearsed. His hand goes here, hers goes there, they turn,

lift to the ceiling, clip here, clip there, bend back down to the

stack .... (I hate to think what the afternoon's work must be like if

they quarrel at lunchtime!)

Not

all of the conversation went as badly as the episode just recounted,

and I spent a very enjoyable afternoon watching the work, and

listening to Misawa-san and his wife Hisako tell me about what they

do. Unlike almost all the craftsmen who have a part in my project

(including me), Misawa-san works standing up. Some of his soft goat

hair brushes are almost a full meter wide, and there is no way to

handle such tools sitting down. A trough full of the warm size stands

at the right end of his bench, and the stack of soft 'raw' washi is

placed in front. He works on a batch of about five sheets at a time,

covering first the front sides, then flipping them over to do the

back, thoroughly saturating each sheet. The morning's stack of a few

hundred sheets is then allowed to stand and 'even out', and in the

afternoon the sheets are hung in pairs from the million cords

stretched across the ceiling. Hisako comes upstairs to help him with

this. Two hands are just not enough for this job, as the soggy paper

must be held very carefully in order not to allow creases to form.

They have been doing this together for a long time, and their 'dance'

is well rehearsed. His hand goes here, hers goes there, they turn,

lift to the ceiling, clip here, clip there, bend back down to the

stack .... (I hate to think what the afternoon's work must be like if

they quarrel at lunchtime!)

The drying proceeds at a natural pace. He never exposes the sheets to the sunshine, as papermakers sometimes do, as this would result in a too rapid drying, and a resulting weakness in the sized sheet. Misawa-san mentally gauges the humidity, and adjusts the window openings to suit. The rainy season is of course a major headache. The size can easily start to decay if left wet too long, as nikawa is made from animal bones, (it is quite similar to the 'hide' glue used by violin and guitar makers).

As I sat and watched him wield his large brush, I was struck by how similar the rhythm of his work is to that of Shimano-san the blockplaner, Matsuzaki-san the printer, Usui-san the blacksmith, Yamaguchi-san the papermaker ... Although his arms are in constant motion, the only part of his body that seems busy are his eyes. They constantly rove over the sheets, looking for tell-tale traces that would indicate where the size was too weak or too strong. There is no stress, no apparent effort, no struggle. The sheets pass under his hands one ... by one ... by one ... by one ... by one ... It sounds immensely boring, but it is not. Those of you who have never done this kind of work can never understand. It is not the infernal, driving rhythm of the factory assembly line, but a rhythm which comes from inside the craftsman himself. Misawa-san stands at his desk, brush firmly grasped in hand ... dip - wipe - stroke - flip, dip - wipe - stroke - flip ...

As we sit chatting later I learn that his work even has an effect on his diet. If there were traces of oil on the paper, the size would not penetrate properly, and the colours in the finished print would be uneven. In order that the sheets of paper are protected from even the tiniest traces of skin oils from their hands, Misawa-san and his wife eat no tempura. A Japanese kitchen without fried foods!

There are quite a number of different costs involved for each of the finished prints that I send out: washi 500+yen, packaging 300yen, part-time helpers 500yen, postage 500+yen, woodblocks 200+yen (per sheet), etc. Among all of these, by far and away the smallest is the fee Misawa-san charges for his work: \60 per sheet. He himself refers to his part as 'ichiban shita', the 'lowest' part of the process. But I cannot carve without smooth woodblocks or without a good blade. I cannot print without a good baren, good washi, or without good sizing. Who among these craftsmen is to be 'ichiban shita'? I am sure you can guess my answer.

I was astonished to learn from Misawa-san that he has never met Yamaguchi-san the papermaker. Decades of work together, and yet all he knows of Yamaguchi-san is what he read in this 'Hyaku-nin Issho' newsletter a few months ago. As soon as I can afford to do it, perhaps for the 'half way' exhibition in January of 1994, I want to bring all these craftsmen together (the men you have read about in this newsletter, as well as the ones who have yet to appear in these pages). I want to stand side by side with them in front of my prints, and I want to show everybody in this country just what a woodblock print really is. It is not Shunsho, or Utamaro, or Hiroshige. It is a craftsman, his mind at rest but his full attention focussed on the work before him, the sheets of paper (or twists of bamboo, or slugs of steel) coming into his hands in a steady confident rhythm, being worked on, and then being passed on to the next man, and the next, and the next. And then finally passing to you, the collector.

After I made my farewell, and walked up the road toward the bus stop, I knew that Misawa-san was probably already back upstairs at his bench, trying to make up for some of the working time he had lost talking to me. But I also knew that no matter how late he became, the rhythm would not vary. Each sheet would still get the attention it needed. The sizing would be done properly. As you hold your next new print to inspect it, spend a minute and think of Misawa-san and his vat of 'crocodile skin' soup. The size he applied to that sheet was actually only needed for the short time that the paper was on my printing bench, and it will gradually disappear from the paper over the course of the next few decades. But without it, and without his skill, your print could not exist. Mr. and Mrs. Misawa, thank you very much.