Visit to ... Gosho-san, the baren maker

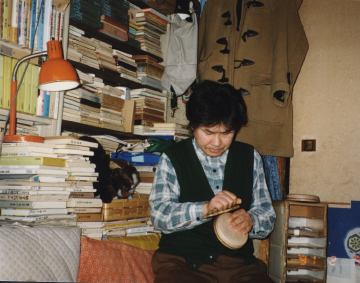

Mr. Kikuo Gosho

I was starting to get a bit frustrated. Perhaps I would not be able to live up to the boast I had made on the telephone, "Of course I'll be able to find your house, don't worry ...." From my home in Hamura to Shimo-fujisawa in Saitama had taken just one hour by bicycle, and it had seemed that there was going to be no problem. But I had now been wandering around the town in ever increasing frustration trying to locate the house, and in my fear of being late I was ready to swallow my pride and ask directions. I pointed my bicycle down a narrow path where a woman was sweeping leaves, and hesitantly asked her, "Sumimasen, Shimo-fujisawa no yon hyaku hachi wa doko ni arimasu ka?" Of course, that turned out to be her house number, and this was my destination. It had taken me a hour to get to their town, and another hour just to find their house.

I was visiting Mr. Kikuo Gosho to see something

of his work, and to place an order for one of his hand-made barens,

the tool used for rubbing the printing paper over the woodblocks. Up

to this point I had been using a varied selection of barens, mostly

student-grade tools that I had obtained from art supply stores. Some

of these had been quite expensive - about 15,000 yen, but all were

less than adequate, and I was growing increasingly frustrated with

using them. There is a well-known saying to the effect that it is a

poor workman who blames his tools for bad work, but nonetheless, you

don't see many professionals using toy tools. Some professional

printmakers had recommended I come and see Gosho-san. This visit was

long overdue.

I was visiting Mr. Kikuo Gosho to see something

of his work, and to place an order for one of his hand-made barens,

the tool used for rubbing the printing paper over the woodblocks. Up

to this point I had been using a varied selection of barens, mostly

student-grade tools that I had obtained from art supply stores. Some

of these had been quite expensive - about 15,000 yen, but all were

less than adequate, and I was growing increasingly frustrated with

using them. There is a well-known saying to the effect that it is a

poor workman who blames his tools for bad work, but nonetheless, you

don't see many professionals using toy tools. Some professional

printmakers had recommended I come and see Gosho-san. This visit was

long overdue.

The house is small, and there is no room for a special workshop. Gosho-san's work is inseparable from his family life. He works on the floor in the center of a six mat room, flanked by his two children's school desks, towering bookshelves, and the usual assortment of Japanese wardrobes. As I enter the house, and walk sideways down a narrow passage, I can see that every inch of space off to each side is jammed with his vast collection of materials related to printmaking: books, tools and prints. He obviously lives for 'hanga'.

His work just as conveniently can be summed up with one word: 'take', the Japanese bamboo (pronounced like the drink: 'sake'), for it is this versatile plant which provides the material necessary for making his barens. A printmaker's baren has three main components, a tight coil made of literally thousands of short thin strips peeled from the outer surface of a special type of bamboo leaf; a backing disk made of dozens of layers of tissue-thin Japanese 'washi', pasted together over nearly a month at the snail's pace of one sheet per day; and finally the covering, a specially prepared, tightly wrapped leaf from yet another kind of bamboo. This 'formula' was developed gradually over a period of some centuries, and has proved to be so well matched to the printmaker's needs that no substitutes have ever been able to replace it. Modern Japanese entrepreneurs have tried dozens of alternatives: molded plastic, rows of tiny metal balls mounted in teflon, and many other ingeneous devices. None of them do the job as well as the traditional materials. Bamboo remains 'king'.

But back to Gosho-san, working on a customer's order. The preparation has been done, the thousands of tiny bamboo strips needed to make the coil all sliced to size and carefully moistened. He sits in front of a low wooden frame and starts lacing the strips together, four at a time. The first ones are tied to a loop on the frame, and then a lightning fast twist, twist, twist, produces the first few centimeters of delicate woven bamboo 'rope'. As the strips in his hand become shorter, new ones are fed into the work. His hands are a literal blur, and I can't possibly see what he is doing. I try counting how many fingers would be needed just to simply hold the growing rope and the clutch of thin strips. I give up at 12. A typical baren will contain 18 meters of this delicate creation, with some using much more. It will take him many, many hours to produce the necessary length. His fingers are covered with areas of tough hard skin at the points where he rolls the strips into tight spirals.

Work on the backing disc takes place simultaneously. Each day, a filmy sheet of washi is added to those glued onto a carved template on previous days. When the required number are in place, a covering layer of silk is pasted over the stack, and this is topped with rich black Japanese lacquer, a finish just like that which we see on expensive laquerware. This month, he will make a total of six of these beautiful tools, each of which will go to a highly appreciative customer, who will treasure it for a lifetime.

After some discussion of size, and details like the number of windings in the coil, I place an order for him to make me one. The price will be 50,000 yen, which although it sounds expensive, is actually a bargain considering the amount of work I will be able to do with this tool over the coming years. He promises that it will be ready in about six weeks, and I make my way home, a little more directly than I came.

...

His phone call finally

comes (I had been sleeping by the telephone!), and Michiyo and I

cycle over to pick up the finished baren. After nine years of

struggling with poor tools - I have never felt anything like it. This

is the way to really feel appreciation for a good tool: to go through

a training period with 'average' equipment, and only when you have

developed some feeling for 'how it's done', to step up and receive at

last your 'real' tool. This baren will be my partner for many years

to come. All the prints you have been receiving from me this past

year have been printed by Gosho san's handiwork.

His phone call finally

comes (I had been sleeping by the telephone!), and Michiyo and I

cycle over to pick up the finished baren. After nine years of

struggling with poor tools - I have never felt anything like it. This

is the way to really feel appreciation for a good tool: to go through

a training period with 'average' equipment, and only when you have

developed some feeling for 'how it's done', to step up and receive at

last your 'real' tool. This baren will be my partner for many years

to come. All the prints you have been receiving from me this past

year have been printed by Gosho san's handiwork.

The professional printers I visit occasionally in Tokyo all have quite a collection of barens, thin ones, thick ones, with heavy or light coils, etc. They reach for the one that best suits the particular job at hand. In the future (near, I hope), when my skills have developed somewhat further (and when my budget allows), I will be back here once more, to watch Gosho san's flying fingers weave some more of his magic bamboo rope. If smooth deep colours are finally becoming apparent in my prints, it is in large part due to the hours he spends crouching over his work, endlessly twisting, twisting, twisting, those little pieces of the amazing bamboo. Gosho san, for your hard work and dedication, thank you very much.