Craftsman Carves Poetry in Wood

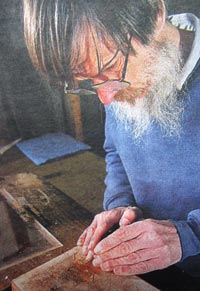

"I am not an artist," says woodblock carver David Bull. The 40-year-old Canadian distinguishes himself clearly from the creative talents who produce the original drawings for woodblock prints. "I am a craftsman." he says.

Born in England and raised in Canada, Bull was originally trained as a classical flutist, and for some time pursued a career in music, which ranged from making classical guitars to conducting youth orchestras to playing bass in a rock band.

It was in 1980 that he made his first woodblock print. Shortly before, he had met the woman who was to become his wife, Japanese Michiyo Otomo, while travelling across Canada by train. His interest in things Japanese blossomed. He worked independently for a while, learning the technique of carving and a three-month trip to Japan in 1981/2 gave him the chance to meet professional printmakers and improve his knowledge of the basics.

In 1986 he finally moved to Japan with his family to be where he could learn directly from the masters, and began to make rapid progress. Three years later he began his great project: the recreation of 18th century ukiyo-e artist Katsukawa Shunsho's "Hyakunin Isshu" series.

The "Hyakunin Isshu (One Poem Each From One Hundred Poets)" are part of Japan's literary canon. Everyone knows of them; most people have memorized a few of the poems, and many people have all one hundred by heart. The popular game of karuta is based on them: One person reads the first part of a poem while players compete to identify it and select the corresponding card from the deck of a hundred scattered on the floor.

It was in fact the game of karuta that first aroused Bull's interest in the "Hyakunin Isshu", but it was the sight of Shunsho's prints that inspired him.

"They were reproduced at a very small size and were hard to see clearly, but one of them, Emperor Tenji, was shown as a full-page illustration. I thought it was fantastic, and decided to explore these images further," Bull reports.

He tracked the original prints to the Toyo Bunko, a Tokyo research library, which had a complete set, and was able to gain access to them. The authentic, original 18th century prints captivated him, and for the first time the idea of making a reproduction of one of them came to him. He got a full-size copy of the Emperor Tenji print and began his first block. It took a full year.

The results of the first block convinced him. He embarked on a series of ten, which rapidly became a determination to reproduce the entire 100-print series. Somewhat to Bull's surprise, the Toyo Bunko proved cooperative. The project went forward at the rate of one print a month, 10 prints a year. Today he has completed the first 30 prints, and expects to complete the whole project in 1998.

The original printmaking

process involved taking a hand-drawn original on tissue-thin paper

and pasting it (a delicate, skilled job) face down on a smoothly

finished block of cherry-wood. Bull pastes a thin sheet of

washi paper onto

a regular sheet of copier paper and then photocopies the original

design onto the washi tissue. Very carefully he peels it off the

copier paper and pastes it onto the block.

The original printmaking

process involved taking a hand-drawn original on tissue-thin paper

and pasting it (a delicate, skilled job) face down on a smoothly

finished block of cherry-wood. Bull pastes a thin sheet of

washi paper onto

a regular sheet of copier paper and then photocopies the original

design onto the washi tissue. Very carefully he peels it off the

copier paper and pastes it onto the block.

The carving process is, of course, crucial, and it is here that Bull feels he has made the greatest progress. Since the pictures are in colour, multiple blocks must be carved, one for the outlines and another for the coloured parts.

Finally the block is inked, a snowy sheet of washi is carefully placed atop it and smoothly and evenly pressed down with a special pad, the baren. Each coloured section must be done separately, and the paper's registration must be exact to keep the colour from overflowing the lines.

In the classic production process each of these tasks is undertaken by a separate craftsman, and some, such as the carving of the block, might be further broken down with the master doing the head, a journeyman the body, apprentices the background and so on. The tools and materials, such as the baren and the ultra-smooth cherry-wood block, are the products of further skilled crafts.

Many of these crafts are dying out, practiced only by old men with no apprentices, and the few remaining woodblock printmakers must combine tasks that once were separated. The impending loss of such vital crafts as baren-making threaten the continuation of the tradition. Bull admits that when many of these men have passed on, the tradition will probably be at an end.

Bull, however, professes no concern over this eventuality. "I am not a crusader," he says. "These things have their time, and if that time has passed, then so be it."

As yet though, the time has not passed.

TV Listings

The 'Woodblock Shimbun' has a full selection of TV programs on file. Videos available include some of David's news appearances, complete feature programs, and some short documentaries on his work. The files are in QuickTime format, and can be easily viewed with your browser.

Program listings are on the Index page ... ![]()

David Bull, Woodblock Printmaker

When I arrive at David Bull's home in Ome in Tokyo's western suburb on a cold but sunny morning in late March, he is checking a huge delivery of kiri wood boxes from China. But this time he is not quite satisfied ... (2007)

Full Story. ![]()

David Bull: Woodblock Print Artist

"Japan is such a fascinating country! Individual energy is balanced, so that individuals and society operate in step with each other. I'm not going home to Canada. I'm grateful if I can carve woodbIocks, and I'm delighted to see my skills improve - nothing gives me greater pleasure!" The enthusiasm shown by David Bull (47), an English-born Canadian, is enough to make any Japanese happy. (1999)

Full Story. ![]()

In the wake of Hokusai

From behind his shaggy beard, affable British-born Canadian woodblock printmaker David Bull ended our interview at his studio in western Tokyo with what sounded like a challenge ... (2008)

Full Story. ![]()