Wood Engraving

Although Mr. Eric Gill in his introduction has explained that this book is not a treatise on the art of wood-engraving, I feel constrained to add a chapter to the present edition of the work, chiefly on the past and modern styles of wood engraving; also to give some information to the younger craftsmen, some of whom, having lived only in an age of photo-mechanical reproduction, are quite unaware of the important part that wood engraving has had in the past for the purposes of book-illustration.

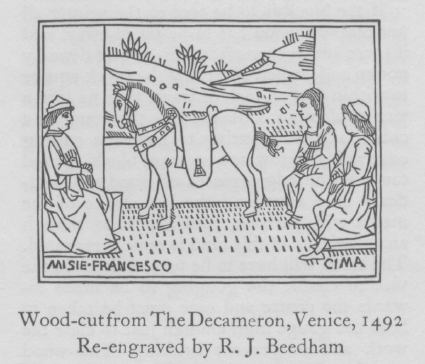

It is a very old craft, older than bookprinting from type. It quickly became the chief means of decorating and illustrating books, and continued to be so until the invention of photographic processes, which, for general purposes have supplanted it. Some of the old blocks, cut in simple outline, fit the printed page in a most admirable manner ; in their particular style they have not been surpassed. An example of this is the re-cut from The Decameron 1492.

These early blocks were all cut on the long grain of the wood, a method that continued until it was discovered that the end grain was a better medium for cutting of fine lines for shading or outline.

It is a disputed point whether artists like Durer or Holbein engraved their own work. It was probably left to the expert to cut in faithful facsimile the drawings done by the artist on wood. With a few notable exceptions, this method of the division of labour, the artist being one person and the engraver another, continued until wood engraving was supplanted by process. For reproductive purposes it was a natural division. After that a completely new style of engraving, that of the present day, came into being.

Thomas Bewick was one of the great exceptions to this division of artist and engraver. Not only did he engrave his own drawings, but he evolved a completely new style. He abandoned elaborate cross hatching, and for the most part cut in the most direct and simple way. Nevertheless, for ordinary reproductive purposes the artist and engraver continued to be different persons; the artist continued to draw on the wood, filling the shading with a wash of Indian ink and finishing by means of pen or pencil lines, or perhaps using the pen alone, but whether drawn by pen or pencil the engraver faithfully reproduced it, line by line. This necessitated great skill on the part of the engraver, for the merest thickening or thinning of the lines altered the effect of the drawing. But sometimes the drawing was done by wash only, in which case the engraver kept as nearly as he could to the shade or tone of the original without the aid of cross-hatching.

This continued until photography made itself felt. It is remarkable that a vast industry, of which the cinema is the latest development, should have arisen as the result of the discovery that certain substances changed their colour and character in the presence of light. It first greatly influenced wood-engraving and finally ousted it as a means of reproduction. Photographers found a way of photographing on to the wood not only drawings but other photographs, and the engraver had to adjust his style to the new medium, for to cut direct from a photograph was very different from cutting facsimile from a drawing. The black lines of cross-hatching disappeared and white lines took their place. Whenever possible a white line was cut and cross-hatching, where it was necessary, consisted of white lines crossing each other. Not only so but a method of cutting short white lines or dots, known generally as stippling, came to be used.

Reproductive engraving speeded up and became a miracle of skill. The use of stipple reached its outstanding development in the work of the American, Timothy Cole. In his engravings of the Old Masters he got amazing effects of atmosphere by means of stippling alone.

The same photographic influence made itself felt amongst the commercial engravers of machinery. The black outlines of the machine became altered to white lines whenever possible, and as in the pictorial field, the style became completely altered. Here let me say that the engraving of machinery for commercial catalogues is one of the most exacting forms of engraving that I know. As a means of showing the object perfectly it holds its own to the present day. There are a rapidly dwindling few who still manage to get a living from it.

The great skill of the reproductive engraver was amazing. On the staff of some of the periodicals, where speed joined to excellence of cutting was essential, there were engravers who could cut a good portrait in two hours, and this in the style just described, line upon line in the perfectly free precision of the time. But this skill of the old reproductive engraver, skill largely for its own sake I fear, made more easy his undoing. Individuality became partly lost in the skill of technique. It sometimes seemed as if he were imitating his great competitor, the process block. The Americans were, I think, great offenders in this. Though a most lovely craft, wood engraving, just before it was superseded by process, had not within it sufficient originality and power to hold its own. It was largely reproductive only the real artist was too often left out. Process developed rapidly as the more effective way of reproducing originals of one sort or another, and the reproductive engraver was bereft of his craft. The output of engravings had been enormous. Some of the old-established printing and publishing firms cherish their old wood blocks they belong to the furniture of the past. Others sold their blocks to the boxwood merchant, not by the block but by the ton!

The period just preceding the influence of photography was one, in the writer s opinion, when reproductive engraving reached its highest level for book illustration. The engravings of this period, if properly printed, appeal for the quality of their softness, their skill, and a sweetness of effect seldom accomplished by the modern style. In many of the volumes of this period are wood-engravings unequalled in their fidelity to the objects shown, and that have a beauty not surpassed by modern or any other engraving. But the days when they were engraved are long since past. We wait again for their revival, which I believe will come, for it is too good a thing to be entirely lost. But it cannot come as it came before: that never happens. The difference will be that the artist will do his own engraving. There are engravers of the present time, who, almost unconsciously, are doing work much in the style of this period.

The modern revival of wood-engraving, which came just after the war, is quite different in style from any that preceded it. The artist and engraver are now one, as they should be where original work is to be done, and every exponent of the craft expresses his or her own individuality. The technique of the old school was swept completely away. 'Start engraving with an axe' was an exhortation overheard, and some of the earliest examples, with their masses of unrelieved black, rather look as if they had been engraved by that implement. Design is the outstanding quality of the present style. Twenty years has brought command of the engraving tool and now most excellent work is produced with the originality of the artist-craftsman upon it. The early crudeness having gone, the modern engraver brings to the printed page a decoration outstanding in effect. Amongst the mass of process reproduction is the Wood engraver, engraving his own designs, thereby expressing an originality which will most certainly mark the present age of book production as something well worth examination. It is therefore essential that the modern engraver design his own engravings and he will select the kind of tools which will best express his own individuality, for it is this individuality of the artist which alone amongst all its competitors will keep alive Wood-engraving as a vital craft.