How I Make Woodcuts and Wood Engravings

THE WOODCUT IS CUT WITH A KNIFE in a block of wood with a grain running parallel to the printing surface. Such a block cannot be engraved, for the graver is not able to cut clean across the grain, but will merely tear up the fibres of the wood without removing them.

Many kinds of wood are suitable, but the most satisfactory are, in the order given, pear, plum, maple, beech, poplar, cherry and birch. Pine and fir can be used only in the execution of a greatly simplified black-and-white style, where the impression of the coarse and irregular grain of the wood is not only unavoidable but actually desirable. The very flaws and knots can heighten the bold effect of the picture. The charm of these natural materials, however, can only be brought out by supreme performance. Only a master can avoid the descent to the cheapest effects.

The woodcut is the newest medium among the original graphic arts. In it the modern artist finds the means of stylistic experimentation - a means wherewith to express with strength and precision exactly what he has in mind, and give his pictures literary content without erring in taste. But the reverse must also be kept in mind - that the very ruggedness of the medium may lead to a mere accumulation of bombastic effects.

The woodcut, technically the most primitive and most robust of all the manual processes, requiring the greatest strength of arm and hand, and richest in stylistic problems, exerts an irresistible attraction on those artists who wish to avoid being facile and equally to avoid repeating themselves ad nauseam or making a mere formula of their work; who delight to produce with difficulty; who want to express themselves when and how their talent demands, even in dark and sinister moods, and whose artistic character is based on the joy of story-telling and the love of working with their hands.

If, in deciding upon the artistic medium to be used, there is a choice between charcoal drawing and woodcutting - the first of which is quickly produced with slight manual effort, while the second requires strenuous hand work and a considerable expenditure of time - then there is a factor underlying the decision which definitely challenges thought. The artist makes a real choice only in those instances when it is not a matter of indifference to him which medium he uses. He is like a composer who must decide whether his musical concept demands a flute or a viola to give the proper color and character.

The natural language of the woodcut is black-and-white surfaces almost without between-tones. To express this language the actual hand work is the important thing. Inserting the knife to effect a sharp separation between two planes is certainly, so far as touch is concerned, a stronger, more expressive manner of working than evolving a black-and-white design on a sheet of paper with pen and ink, for the knife, as it divides, introduces a third dimension, depth. The visual effect of the two techniques may be about the same. But the way of the knife in the wood is much more time-consuming and arduous. If the final result is not stronger, more expressive, stylistically more significant, then the detour has been a useless expenditure of time and of energy.

It follows that this difficult path will be preferred by the artist who not only loves the stubborn, intractable nature of the woodcut, but who seeks it out in order to achieve a deliberate effect; who knows the deep inner excitement of holding in his hands the still unmutilated block and making that first cut which determines all that follows; who is aware of a deep spiritual significance when the creative mood, combined with the expression of the strength of his arm and hand, gradually intensifies into a delirium of concentration; who, as he cuts through the grain, sees in a flash before him the very tree whose wood has now become the medium for the realization of his dream.

I should now like to reveal some of the intimacies of creation which only the artist can know. I shall touch upon them now and again in what follows, and I can only hope to succeed in handling these delicate matters without false sentiment.

The

contrast of black and white cannot be brought out more sharply than

in the long-grain woodcut. A similar effect in wood engraving would

be attempted only in very small format (e.g., Masereel's Book of

Hours). Technically the woodcut is not very well suited to small

formats; the only limitation that can be set to its largeness is that

the whole must be taken in at a glance. [Illus. No. 12.] In

woodcutting the artist strives for simplification of form and for the

reduction of all tone values to two denominators, black and white.

The production of between-tones, easily accomplished in charcoal

drawing, is certainly not forbidden, nor is it in any way detrimental

to the style. But it requires a skill in handling the knife which

must not be underestimated, and a knowledge of what is of real value

in the final proof.

The

contrast of black and white cannot be brought out more sharply than

in the long-grain woodcut. A similar effect in wood engraving would

be attempted only in very small format (e.g., Masereel's Book of

Hours). Technically the woodcut is not very well suited to small

formats; the only limitation that can be set to its largeness is that

the whole must be taken in at a glance. [Illus. No. 12.] In

woodcutting the artist strives for simplification of form and for the

reduction of all tone values to two denominators, black and white.

The production of between-tones, easily accomplished in charcoal

drawing, is certainly not forbidden, nor is it in any way detrimental

to the style. But it requires a skill in handling the knife which

must not be underestimated, and a knowledge of what is of real value

in the final proof.

No other artistic process is so directly dependent on the nature of the technique as the woodcut. The straight edge of the knife has an almost malicious tendency to persist in the direction of its insertion. Only after long practice can one succeed in cutting curves. And cutting with the grain of the wood has a different feel than cutting across it or diagonally to it.

The cutting of closely parallel lines with the knife which together will give the half-tone effects [Illus. No. 13] is one of the most irksome tasks that an artist can set himself. A similar effect can be obtained more quickly and with less effort by using the gouge, but the result will not exhibit the strength of style attained by cutting with the knife.

I need not dwell on linoleum cutting as practice for wood-cutting. The simplicity and effortlessness of its technique places it within the reach of any beginner or dilettante.

Linoleum can be bought in any department store cutting off from the roll in large quantity or in art material stores mounted on a woodblock (type high). In the second case I advise to buy plates which are not white covered. The surface of the linoleum plate should have the same color as the cut. The white skin makes it easier indeed to recognize the pencil or ink drawing, but more confusing for your eye when you start cutting, because of three different shades: black drawing, white skin and color of the linoleum. Linoleum needs a little less pressure than wood.

Strangely enough, in the very nature of the woodcut lies the ability to demonstrate the connection between a technically primitive material and the abstraction of meaning achieved by it. Or should this ability portend just the opposite? It is the same inexplicable phenomenon that in music allows wood, gut and hair (the acoustical equipment of a stringed instrument) to interpret a Bach fugue, the highest form of spiritual abstraction. The most erudite explanation would still leave me far from satisfied.

A few technical instructions now:

- Tools: knives and gouges. [Illus. No. 14.] These are used on all long-grain blocks and linoleum.

- Whetstone. To sharpen the knife, two drops of machine oil on the stone. Also, water or spittle.

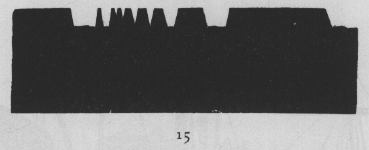

In cutting, insert the knife so that the surface or line to be outlined by the cut widens slightly at the base, somewhat in the form of a stone or concrete dam. here is a cross-section of a block, somewhat enlarged. [Illus. No. 15.] Cut deep enough. This makes it easier, later on, to rout out the areas that are not to print, as the wood near the edge of the cut tends to break off of itself. This will avoid the danger of the knife hitting under the dam-shaped foot of the line or surface and injuring it or even breaking it away altogether. To rout out larger areas it is better to use a gouge.

During the cutting, the block lies flat on a steady table, not on a leather sandbag like the engraving block. Particular people like to place a thick, even piece of cloth between the block and the table. It is obvious that the very slight rocking and yielding of this foundation pad will give a pleasant elasticity to the hand guiding the knife, and yet the block will not wobble.

In wood-engraving, as was just noted, the cross-grain block lies on the leather sandbag and is turned so that the plane can be worked on from all directions. The long-grain block for woodcutting remains flat on the table. But since it, too, must be turned during the work, there is still to be invented and manufactured a vise in which the block will be firmly held so that the knife can be applied from various angles. This vise will have to rest in the middle of a round or square board about two armlengths in diameter, the turning-screw affixed with considerable tenacity. But so many artists have invented and constructed gadgets, and, for all that, their pictures don't seem to turn out any better.