How I Make Woodcuts and Wood Engravings

THE UNDERLYING DESIGN of any woodcut or wood engraving is first sketched either on paper or directly onto the block with soft pencil or India ink. The second method is preferable, provided, of course, that it is unimportant whether or not the picture appears reversed in the proof.

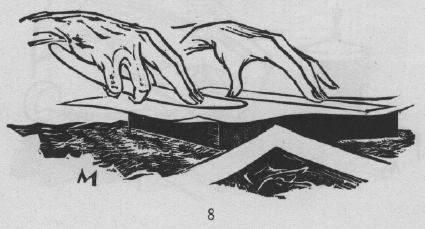

Drawings which must not be reversed have to be mechanically transferred from paper onto the block, so that the final result will be an exact reproduction of the original. To avoid the wasteful process of tracing, an impression of the original drawing is made directly on the block. To do this the woodblock is covered with a very thin coating of any kind of soap, softened by the wet balls of the hand. The pencil drawing is then laid on the block face down and lightly fastened to it at two corners. Pressure from a hand-press or rubbing with a bone folder brings out an exact tracing on the block. [Illus. No. 8.] If the pencil used for the drawing is not too hard, the soap will retain a great many of the graphite particles. (Use Pencil No. 3B.)

Grounding the woodblock with a white film, as was formerly done, is not advisable. The between-tones which result are irritating to the eye in the course of further work on the plate, for there will be three shades: the black of the drawing, the white of the film, and the slightly darker color of the wood which comes into play at the first cut.

Transferring a sketch by tracing is always distasteful to an artist. The freshness of his work is lost in mechanically going over the drawing and sharpening the lines with a harder pencil, and placing the carbon paper between the drawing and the block results in a copy whose lines are lifeless. The drawing which appears on the wood is perfectly correct in outline but devoid of expression. The development of the work sustains a crippling blow. It is a deficiency to which beginners are especially subject.

This practical knowledge, though apparently of slight importance, was not gained overnight. It is an example of the close interdependence of a very simple technical process and a highly emotional and spiritual experience. It is in dealing with just such details that a teacher should find a field of useful activity.

After the transfer of the sketch onto the block, the composition is strengthened with black India ink, using pen or brush.

Then the surface of the block is darkened with a dilution of India ink, printer's ink or graphite powder, to such a degree that, while the drawing remains visible, the deepest possible tone is obtained, in order to get the contrast between the darkened surface and the natural color of the wood which appears in cutting.

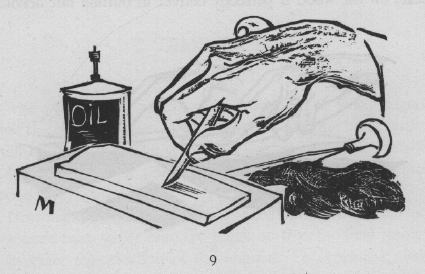

Knife, gouge and graver must be well sharpened - a skill which must also be acquired. [Illus. No. 9 shows the sharpening of a graver.] Most beginners ruin their tools, and it is often hard to determine whether an unsuccessful piece of work is due to lack of control or to a dull knife - to the artist or to the tool.

The artist must sit so that the light comes from the left front, or, in the case of a left-handed person, from the right front. Eyes must be shaded against the source of light; the block should be about ten inches away from the eyes; both elbows should be outspread on the table, giving the effect of a brooding swan. All remains of previous work must be cleared away.

And now the artist can begin to cut or to engrave - where and how is his concern, and each one does it differently. But now he must not be disturbed.

When he feels that his work is ready for printing, he washes off the block, first with a rag lightly moistened with benzine (not turpentine), and then with one dampened in water, to get rid of the traces of India ink. Wood is porous and tends to absorb water and become soft, which is not good for the printing.

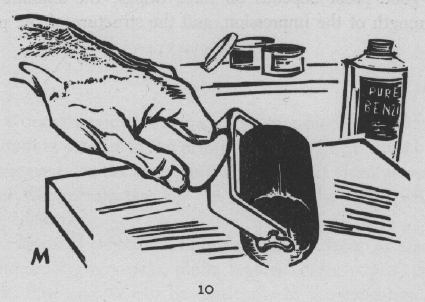

In a few minutes the block will be dry. It is then carefully brushed in all directions, but not, of course, with a steel brush. Then the artist takes printer's ink from a can or tube, spreads a wide strip of it with a spatula on a smooth stone or glass plate, rolls out the color evenly with a printing roller into a rectangular field [Illus. No. 10].

The substance of a roller or brayer is a composition of glue and jelly (not rubber). Rollers do not like sun rays and heat. Then transfer the ink to the block with the roller, being careful not to press too hard. The color spreads most evenly and quickly if it is applied to the block with criss-cross strokes of the roller, lifted at the end of each stroke and set down anew. It is useless to move the roller back and forth three or four times over the same track.

Then the paper is placed on the block and pressure is applied, either with a regular handpress or an embossing press, or, when neither is available, by rubbing with a bone folder, in which case one must be careful to avoid slipping off the edge of a line or surface. The folding bone likewise is used when the artist wishes to get variations in impression from one and the same plate - that is, where tonal gradations are not cut in the block, but are attained by more or less pressure of the hand. This gives the effect of painting. This method must be used sparingly and for highly special effects, and should be avoided altogether by beginners. A good proof depends on three things: the amount of ink, the strength of the impression, and the structure of the paper.