How I Make Woodcuts and Wood Engravings

IN WORK WITH COLOR the same principle holds true for both the woodcut and the wood engraving: as many blocks as there are colors.

The colored woodcut attains its full stature in the work of the Japanese. There is nothing comparable to it in style or technique. Far as the European excels in the mastery of the black-and-white woodcut, just so far does he lag behind in the use of the colored woodcut. There are a few exceptions to this. Among them I should like to mention the work of Richard Floethe and Charles Smith, who have caught the true spirit of the colored woodcut: the equal importance of all the blocks which make up a color print. The print made with several plates, but in which a key-plate, in black, predominates I do not consider to be a colored woodcut, for the colors might just as well be added with a brush, or the key-plate allowed to stand alone. Not the number of plates, but their real necessity, is the determining factor in the colored style, and that is the only thing that counts.

The charm of a four-voice composition lies in the way each voice adds its separate color to the whole. The harmonious accompaniment of three voices to one leading voice is not, strictly speaking, a four-voice composition. style of his picture. With but few exceptions, then, the colored woodcut in Europe has produced a large but somewhat feeble progeny - insignificant in style, more or less crude in color. The best of them are still inferior to the Japanese. So the colored woodcut as a whole is not comparable in importance to the black-and-white.

The colored woodcut and engraving demand great clarity in the arrangement of colors, for the bringing together of a number of colors into a complete picture is a slow sequence in contrast with painting in oil or water color. What the composite proof shows to be lacking in any one plate it is then too late to correct. In painting, the artist can jump from one color to another in a comparatively short time, which is indispensable as groundwork for composition in color, but this is not possible in woodcutting or engraving. Of course, the different colors can be tried out alongside of one another on the inking stone, but the color values of three or four plates printed on top of each other will only be seen in the final result. If this is not as desired, all the plates must be printed over again. Obviously, a woodcutter who can do this must also be a painter.

In modern colored woodcuts either water color or oil paint (printer's ink) is used. Water color is opaque, oil is transparent; water color is more fluid than oil.

If the pigment of water color is too strong, it can be thinned with water or glycerine. If the pigment of oil is too strong, it can be thinned with transparent (not opaque) white. Also, in both cases, it is possible to obtain a light shade by inking the stone with correspondingly less color.

Oil color can be made opaque by mixing opaque white with each color used. But here we are dealing with special cases.

Knowing the chief characteristics of water and oil color, as described above, the woodcutter can now determine on the color

When water color is used the color structure will be produced chiefly by the placing of colors next to one another. Because of the opacity of the colors, obviously if they were superimposed upon one another, the last printed would predominate. When oils are used, the structure is produced by the overlapping of the blocks. A wealth of color may be obtained in this way because of the gradations within the overlapping plates.

These basic differences in the use of water color and oil do not, of course, preclude certain modifications. Changing the consistency of either will affect the number and distribution of the plates; it is possible to make a water-color woodcut composed of several superimposed blocks and very much thinned color, or an oil color woodcut with colors printed alongside each other and the demarcations heightened by an admixture of opaque white.

Both kinds of color may be had commercially in tubes or cans. Our color chemists are experimenting with a water color for relief printing which will have the advantages, heretofore monopolized by oil, of being less fluid and more transparent. This will mean that water color can be used for colored wood engravings, too, without fear that the finest line groups will become choked with the color.

The thicker the color, the less is required. The superimposing of colors rests on this hypothesis.

Every technical variation is justified insofar as it contributes something of its own. The same holds true of style. The colored wood engraving, as opposed to the colored woodcut, shows an enrichment of the tonal variations within each individual plate. Therein lies its peculiar charm. What is gained in the way of color nuances when these already shaded plates are superimposed upon one another is not hard to imagine. But this wealth of color tone must be produced with a smaller number of blocks than the woodcut requires. A colored wood engraving in four or five plates is so artistically inclusive that the addition of another plate may tend to weaken the color effect, dulling it to the eye because of the very oversaturation of color particles.

The colored wood engraving is an entirely new phenomenon among the original graphic arts. From the point of view of technique only, perhaps the work of a little known artist of the reproductive school, Krueger, might be considered as the product of a forerunner. Around the turn of the century Krueger was occupied in reproducing in color the great oil paintings of the sixteenth and seventeenth century. He was an artist of our generation with an unequalled love of craftsmanship. His work represents the dividing line between sedulous reproduction and artistic creation. A unique case, so far as I know. I assume that this artist, unrecognized during his lifetime, has received his due of appreciation somewhere in the history of art.

In our times the colored wood engraving appears almost entirely in book illustration, and there it has found its proper sphere.

Among the few of our book illustrators who have worked exhaustively in this field, the name of the Frenchman Fernand Simeon must be prominently mentioned. The colored wood-engraved illustrations of this distinguished artist represent, in my opinion, the height of the enchantment that can be evoked by this medium. Simeon's colored prints (see 'Jean des Figues' and 'Chevre d'or') stem directly from painting. They possess the greatest charm that a print can have, combining the highest degree of artistry with a fresh technique, free from routine, almost clumsy. How different they are from the work of some of our well-known contemporaries whose technical virtuosity and ossification of style through eternal repetition lead finally to a condition of spiritual devastation.

The novelty of the colored wood engraving lies in its style as well as in its technique. Here the use of the multiple liner is most important. I have already mentioned that each individual plate in a four- or five-color engraving can show within itself a greater or less degree of tonal variation, depending for its position and the direction of its lines on the desired tonal color of the composite print.

Since the style of the colored wood engraving is polyphonic and is achieved by all the single plates playing each its part, the engraver, when he considers the color sketch which forms the basis for his engraving, faces the ticklish problem of deciding which plate should come first. Experience will teach him to choose a color which appears most frequently in the picture, and which will be of medium, or light tone value - never dark. The darkest color he will keep for the last, using it to put the final accent on the picture. This procedure is exactly the opposite of that used in the earlier woodcut or engraving, which began with a key-plate and followed on with one or two plates of a purely supplementary color character.

After the earlier colors have been printed the artist will see where an accent is needed to round out the color harmony. The essence of accent lies in its sparing use. If he began with the darkest color he would always be tempted to employ too much of it because of the emptiness of the picture at that stage. It is a wearisome mental process, in engraving this darkest plate as the first, to retain constantly in the mind's eye the total color-composition; the danger is great that this darkest plate will include too much, and perhaps even become a key- or outline-plate. This would upset the stylistic conception. On the other hand if, after the first composite proof, one of the individual plates appears to contain too much, this can easily be corrected without infringing upon the character of the color style.

The multiple liner, with its wide range of tone values, is the implement which, with the least effort, produces the desired artistic effect in each individual plate as well as in the harmony of the whole. And, confidentially, a successful work of art is produced not so much through the virtuosity and capacity for the work of the artist as the uninitiated seem to think, but rather through the logical cooperation of certain determining factors which underlie the solution of any artistic problem. Even after years of experience the artist is taken by surprise by almost every work successfully completed in a new technique of which he had not dreamed before. This surprise always gives him deep if brief gratification, and remains the finest reward for a completed job.

A few further comments are necessary on the technical procedure in making colored wood engravings.

The colored wood engraving differs from the one-color engraving in that it is practically essential to have a preliminary color sketch. This sketch will show the direction of the color limitations. It is not the original; it is merely a visible guide for the mental concept of the finished engraving. The original is present in the mind of the artist, and first takes visible form as the finished print. I do not think it will harm to repeat this again. The fact that we artists are still often asked 'Did you cut the block yourself, too?' shows how little understanding there is of the true nature of the original graphic processes.

After the first block has been engraved it is inked with the allotted color and printed. Then at inconspicuous points, and as far apart as possible, little holes are made in the wood with the finest needle available. These are the so-called register points. The remaining colors, not printed in the first proof should be sketched in with colored pencils or crayons so that the complete effect is before you. In this way the artist can see whether there is too much or too little in the first plate, as well as judge of its color value. Next he makes an impression of this first plate, in black, on each of the successive plates, and immediately drills the register holes in the wood. This assures the register of all plates in the composite. He engraves the second plate after sketching in, in black ink, what this plate is to contain; then takes an impression of the first and second plates together, and again fills in, in colored pencil, the colors still to come. All the plates follow along in this manner. The process of making combined proofs of all the colors until the final proof is in hand is most complicated and delicate, and often takes longer than the engraving of the plates. The knowledge that two colors of the same tone value when superimposed produce not only a third color but also a distinctly darker shade determines the selection, mixing and quantity of the colors.

The color tone of one plate can ruin the harmony of all the others. If at the end of the process it appears that one of the earlier printed colors is at fault, the whole job goes into the wastepaper basket and the printing starts again from scratch. In most cases, each plate requires a little working over with the graver. In each plate there is apt to be a little too much - far better than too little. When at last a final proof is ready, the pulling of the edition proofs can begin, for the artist no doubt will want to have a certain number of copies. Now he can begin with any plate whose color has been determined, and print the desired number. Each color must dry for a day or two before the next can be added. If the previous color is not dry, the succeeding one will not be completely absorbed. The paper takes its proper place on each successive plate because the register points are marked both on the paper and on the blocks. An imperfect print is the result of pure carelessness. To use other kinds of register depends on the difference of printing presses. I prefer the above mentioned method because of its exactness and simplicity. It is advisable during the printing to lay aside a couple of proofs of each color separately, in case reprints should be wanted at a later date. In making colored wood engravings I use only oil colors (printer's ink).

As with the one-color wood engraving, there are definite limits to the size of multi-colored wood engravings. All the various gravers, as well as every movement and thrust of the hand that guides them, seem to show an instinctive surrender to surface restrictions. The command of space is limited to about the area of half a medium-sized book page. Beyond that size the woodcut in one or more colors is preferable. The tonal variations within each plate in the engraving technique might easily become tedious and boring in a large format. Wherever art begins to take visible or audible form, such limitations of style appear. It is in the stimulating of one's ability to recognize these limitations, and to fulfill oneself completely within them, that the fascination lies.

In choosing wood engraving one chooses the most roundabout way to produce a small colored picture. If the result is not something peculiarly individual, the effort is hardly worthwhile. I think I have made clear that an exceptional expenditure of effort is required for the attainment of this goal. I myself have been working on this difficult project for almost 20 years. Neither before nor during this time have I seen another woodcutter take it up, and this fact has spurred on my original love for this form of graphic art to a sort of obsession, which grows greater from job to job. Perhaps on the whole it might be called crazy, for no similar examples have appeared along the way to afford help, cheer, inspiration, or controls. Aside from the illustrative work of the Frenchman, Fernand Simeon, whom I have already mentioned, I am familiar with modern colored wood engravings only in the works of the Americans, R. Ruzicka and Th. Nason, and they cannot be classified unqualifiedly as such, since the black plate predominates both stylistically and visually in their work. So I feel at once isolated and encouraged. Perhaps the trail that I am blazing will cross that of another still unknown to me.

The two-tone engraving or woodcut closely parallels the multicolored. Needless to say I do not mean the cut or engraving of a key-plate with a supplementary color plate. I mean two mutually complementary plates of equal importance. (As in music, a Bach fugue in two voices.) Here not colors, but tone values, play the chief role:

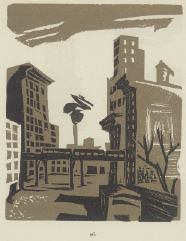

a. The tones are of equal value. For example, let us say the picture is composed of two shades, gray-blue and gray-red. A third shade will appear where the two overlap, gray-violet. We know from experience that it will be the darkest, and this must be taken into consideration in cutting the plates. So, with two blocks, three colors are produced. Since, in engraving, each block may have gradations within itself, even more tones will appear. [Illus. Nos. 25, 25A, 25B.]